Overview

The Second Punic War between Carthage and Rome was costly in both lives and treasure. Rome lost ¼ of her citizens and by the end of the conflict was nearly bankrupt. Her allies were exhausted and at one point in the war told the mother city that they could no longer provide young men for her war machine. But as the winner, the Republic emerged as the dominant power in the Western Mediterranean. The rewards of victory were great. She won the wealth of the Iberian Peninsula, consolidated her hold on Italy north of the Po (Cisalpine Gaul), cemented her hold on Sicily with the storming of Syracuse, and emerged strong enough to take on troublesome expansionist tribes such as the Illyrians on the Dalmatian coast, the ever quarrelsome leagues of Greek city states (Aetolian and Achaean Leagues) and the Hellenistic Kingdoms in the east (Macedonia, Seleucia).

The war itself can be divided into five phases:

Phase I

Hannibal grasps the strategic initiative. He takes Saguntum and marches his army across the Ebro River, over the Pyrenees, through Gallia Narbonensis, across the Rhone, then over the Alps and onto the plains of northern Italy, a distance of 1,200 miles.

Phase II

Hannibal’s victories in northern Italy at Ticinus and Trebia, in central Italy at Trasimene and in southern Italy at Cannae weaken the Roman alliance.

Phase III

Ironically, the defection of Capua, Tarentum and other allies to the Carthaginian side after Cannae causes Hannibal to lose strategic initiative. He lacks the manpower to protect his newfound allies. Whereas before Cannae Hannibal dictated strategy to the Romans, after Cannae the Romans could threaten Hannibal indirectly by threatening his allies. Thus Hannibal finds himself increasingly on the defensive in central and southern Italy.

Phase IV

Publius Cornelius Scipio takes Spain from Carthage, a major strategic shift in material and manpower. Scipio lands in Spain and takes Qart Hadasht (Carthago Nova, New Carthage, Cartagena) the provincial capital of Iberia by surprise attack. He conducts two brilliant battles against the Carthaginian armies at Baecula and Ilipa, wins the loyalty of many Iberian chieftains as well as Massinissa, the Numidian Prince, through effective diplomacy.

Simultaneously, Marcellus is successful against the Carthaginians in Sicily.

Phase V

Scipio invades Africa, forces Hannibal to leave Italy and defend Carthage. He defeats him at Zama. This brings the war to an end.

PHASE I

221 BC

Hannibal Barca Proclaimed Commander-in-Chief of the Army in Iberia

Upon the death of his brother-in-law, Hannibal, now 26 years old, upon taking command of the army, proceeds to conquer and consolidate territory in Spain. All of this activity takes place south of the Ebro River, the demarcation line between the Carthaginian and Roman spheres of influence. Saguntum, a Celtiberian city 100 miles south of the Ebro River, recognized the danger Carthaginian expansion posed and entered into an alliance with Rome. The problem is that Saguntum lies well within the Carthaginian sphere of influence as agreed upon in the Treaty of Ebro.

Ebro Treaty

Rome was busy consolidating her hold on Italy and the Adriatic Sea (conflict with Gauls and Illyrians). So Rome needed peace with Carthage and some predictability as to her intentions in Spain. The Ebro Treaty provided that predictability by dividing Spain into Carthaginian and Roman spheres of influence.

219-218 BC

Hannibal besieges and storms the city of Saguntum, a Roman ally. It takes him 8 months to win the city whose plunder will pay for his troops and fund his Italian expedition.

Hannibal, then, with a massive army of 100,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry, has to fight his way north of the Ebro River, subduing Iberian tribes—the Ilurgetes, Bargusii, Aerenosii and Andosini— along the way, as far as the Pyrenees. He then demobilizes a large number of his troops along with the army baggage train. He keeps 50,000 foot and 9,000 horse. The army is significantly reduced in size and relieved of its baggage train, which makes it more nimble. It is a highly trained, experienced and loyal force.

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. 3rd Edition. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, © 1891 The Riverside Press. Cambridge Mass. USA. Pages 163-176.

Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire (Classics). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition Page 252.

218 BC

Causes of the Second Punic War

- Carthaginian resentment over the harsh terms dictated by the Romans at the termination of the first Punic War

- With mutiny by Carthaginian mercenaries on Corsica and their appeal to Rome for protection, the Romans laid claim to Corsica and Sardinia and demanded an additional 1,700 talents to the Carthaginian indemnity under the threat of war

- Roman fear of Carthaginian resurgence because of her expansion in the Iberian peninsula

- The pro-war party, the Barcids, carried the day in Carthaginian politics when the Romans demanded that Hannibal and his senior officers be surrendered to the Romans for their storming of Saguntum

Strategic Factors at the Beginning of the War

- Roman character showed almost superhuman persistence, even under the most trying circumstances

- The Roman state was geared for war, the Carthaginian for trade

- Rome was distracted by Gallic unrest in Cisalpine Gaul and by periodic Illyrian piracy in the Adriatic

- The Insubres and Boii were waiting for a countervailing force to rally around against the Romans

- Rome had alienated Macedonia and thus had a powerful enemy on her eastern flank

- Rome had control of the seas

- Although Rome dominated the sea lanes, the Carthaginian fleet was capable of engaging in asymmetrical warfare with hit and run raids on the Italian coastline

- The Roman alliance system was strong

- Her manpower reserves were greater than anything the Carthaginians could muster

- Hannibal had no logistical lines of communication; his army had to live off the land and replenish its losses from local populations hostile to Rome

- Spain was newly conquered territory and the Carthaginian hold on that country was tenuous

- The Carthaginians had tough battle-hardened Libyan and Iberian infantry and superior Numidian cavalry

- The Roman legions had formidable heavy infantry but her cavalry was an afterthought

Spheres of Influence during the Interwar Years—Carthage versus Rome

Rome consolidated her hold on the Italian peninsula and checked Illyrian expansionism. Carthage expanded in Spain in order to compensate for the loss of Corsica, Sardinia and Sicily after the First Punic War.

The Second Punic War Begins

After Hannibal takes Saguntum and Carthage refuses Roman demands to surrender Hannibal and senior Carthaginian officers to Roman justice, Rome declares war.

1,200 Mile March to Italy

Hannibal’s march from Spain to Italy can be divided into 6 parts:

- The march through friendly territory, from winter quarters at Qart Hadasht (Carthago Nova, modern Cartagena) to the Ebro River

- The conquest of Northeastern Spain (modern-day Catalonia)

- The relatively easy march across Gallic territory

- Crossing of the Rhone River north of Massilia:

- Manipulation of Scipio and his Roman legions into sailing up the Rhone River in pursuit of the Carthaginian army by having his Numidian cavalry pretend a reconnaissance in strength;

- Effect an opposed crossing of the Rhone River north of Massilia;

- Rapid movement of his entire army until it loses its Roman pursuers

- Crossing the Alps in Autumn via the Col de la Traversette

- Descent into friendly Insubres territory on the Po plain in Winter

Hannibal’s march on Italy

The march was 1,200 miles long over often mountainous terrain, sometimes peaceful, often fighting. The journey can be divided into 6 parts: the 1st through friendly territory; the 2nd, the conquest of what is today Catalonia; the 3rd through friendly Gallic country; the 4th, across the Rhone and outmaneuvering the Romans; the 5th, across the Alps fighting hostile tribes; and the 6th, arriving on the Po plain.

Hannibal’s Itinerary: March to Italy

| Left Qart Hadasht | May 30/June 1 |

| Crossed Ebro | May 15 |

| Reached Illiberis | September 15 |

| Crossed the Rhone River | September 27 |

| Reached Summit of the Alps | October 26 |

The Col de la Traversette

The Col de la Traversette is approximately 9669 feet (2,947 meters) above sea level. Hannibal’s army arrived at the end of October. The peaks were already snow covered. It was the twelfth day of the Carthaginian army’s march through the Alps. The losses, because of the attacks by mountain tribes and because of the treacherous terrain and snowy conditions, were great. Many pack animals and men perished. The troops were dejected and recent landslides had made parts of the pass impassable. Hannibal had to put his men to work building a road that would allow the animals to reach pasturage below the snow line on the Italian side of the pass. The task was completed in three days. By the time they reached the Padus plain (the Po), the army, which had crossed the Rhone with 46,000 men, was now reduced to 26,000; 12,000 African infantry, 8,000 Spanish Infantry and 6,000 horse. The journey over the Alps had taken approximately 15 days.

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891. This edition copyright © 2012 Tales End Press. Pages 228-232.

Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire (Classics). Book III. Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert Selected with an Introduction by F. W. Walbank. Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition. Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Little Bernard Pass

Photo of Little Bernard Pass by Etienne Hessels.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/

ehesselsfotografie/24190702469 Accessed May 1, 2018.

PHASE II

Hannibal Fights in Northern Italy

War with the Taurini

After resting his army, Hannibal offered the Taurini, enemy of the Insubres, an alliance. Being an ally of Rome, they refused. He besieged their major city, Turin, and took it within 3 days. All of the inhabitants were put to the sword. By this action Hannibal terrorized the Gauls who might have contemplated harassing the Carthaginian and thus secured his rear while maneuvering against the Romans.

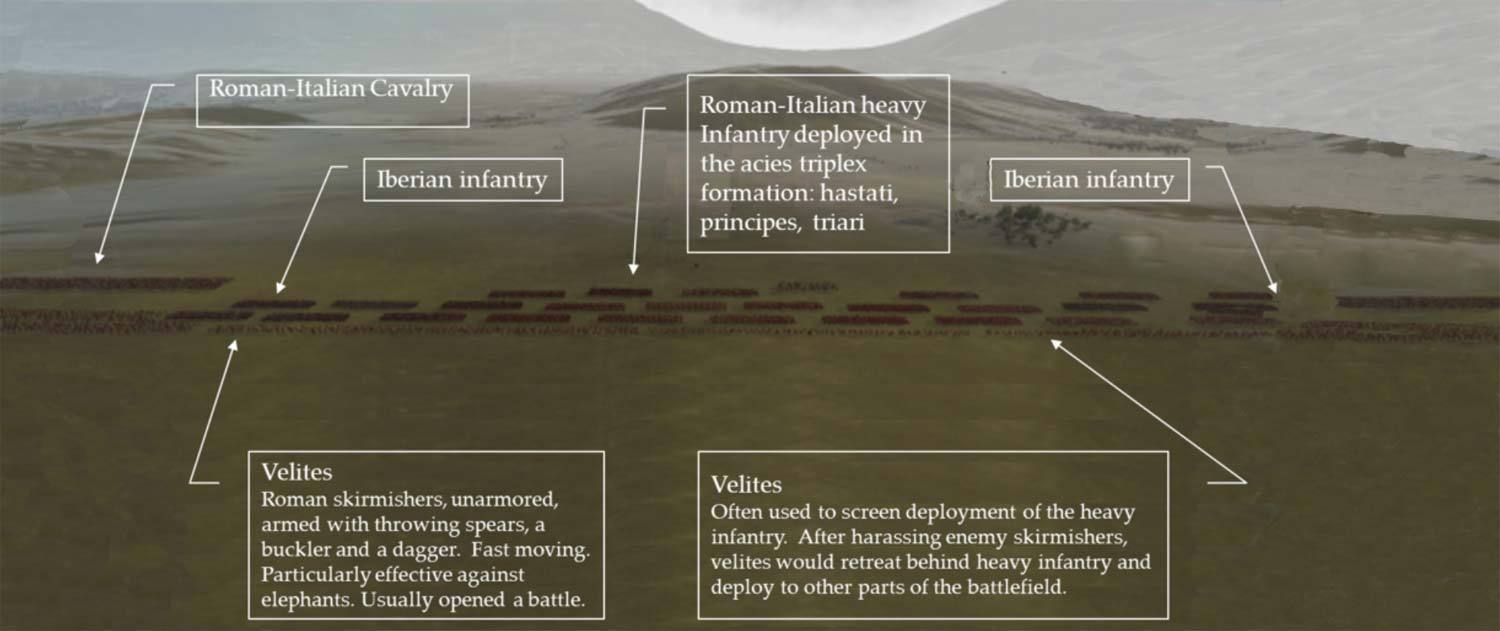

Battle of Ticinus

The battle of Ticinus was fought between Hannibal and the older Publius Cornelius Scipio (Africanus’ father). It was not a full on battle but rather involved elements—the light infantry and cavalry of the Romans and the heavy and light cavalry of the Carthaginians—of both armies. Scipio opened the contest with his peltasts (skirmishers called velites), whose purpose was to attack the Carthaginian cavalry with javelins. Hannibal, recognizing the move, had his heavy Spanish and Carthaginian cavalry charge them. The velites fled behind Roman lines before they could discharge their weapons. The charging Carthaginian and Iberian heavy cavalry then slammed into the Roman cavalry and the fight began in earnest. Scipio was seriously wounded early in the fight. For a while the battle was even but then the superiority of the Carthaginian cavalry began to tell. In the meantime, the Numidian light cavalry swept around the Roman flanks, scattered the velites and hit the Roman cavalry on the wings. The Roman formation disintegrated.

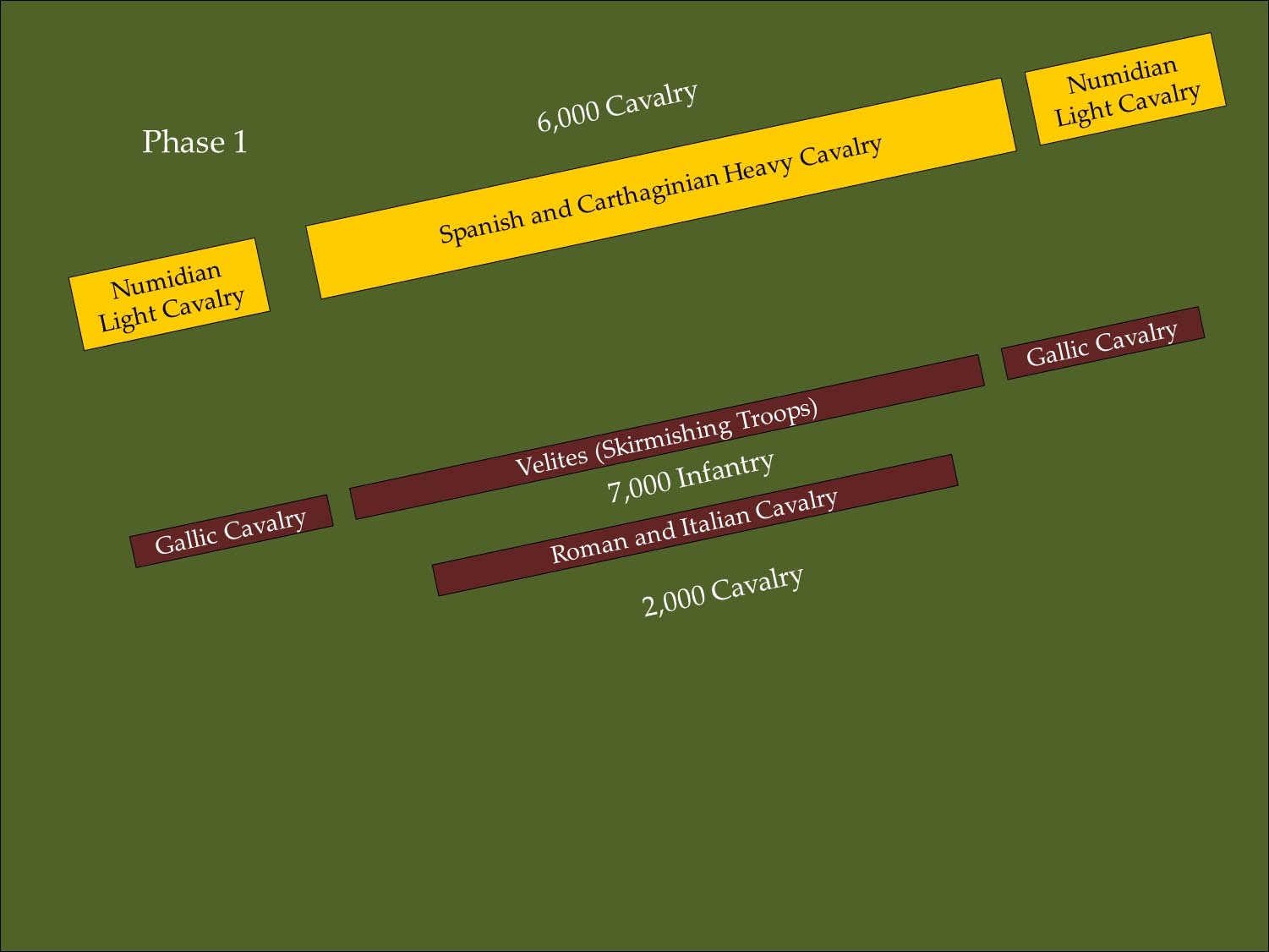

Ticinus—Phase 1

After sending his troops on to Spain, Scipio returned to Rome and then hurried to Gaul in order to take command of the army there. Once there he shadowed Hannibal. As the two armies maneuvered for strategic advantage, two reconnaissance-in-force bodies met at the Ticinus River.

Ticinus—Phase 2

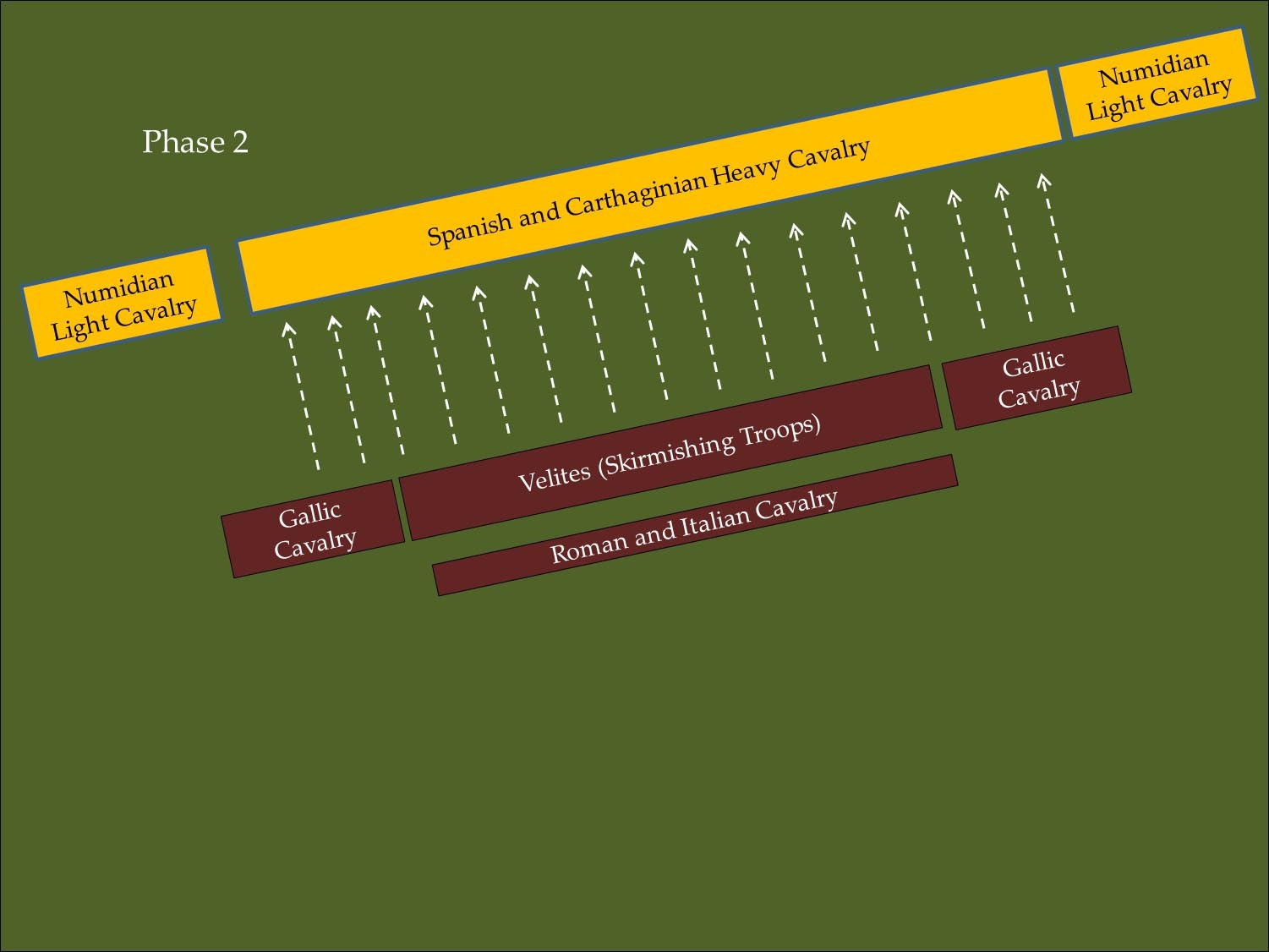

The Romans had more men but the Carthaginians had more cavalry. Scipio deployed his troops in two lines, the Carthaginians in one. Scipio sent his skirmishers (velites) forward along with Gallic cavalry in order to harass the Carthaginians.

Ticinus—Phase 3

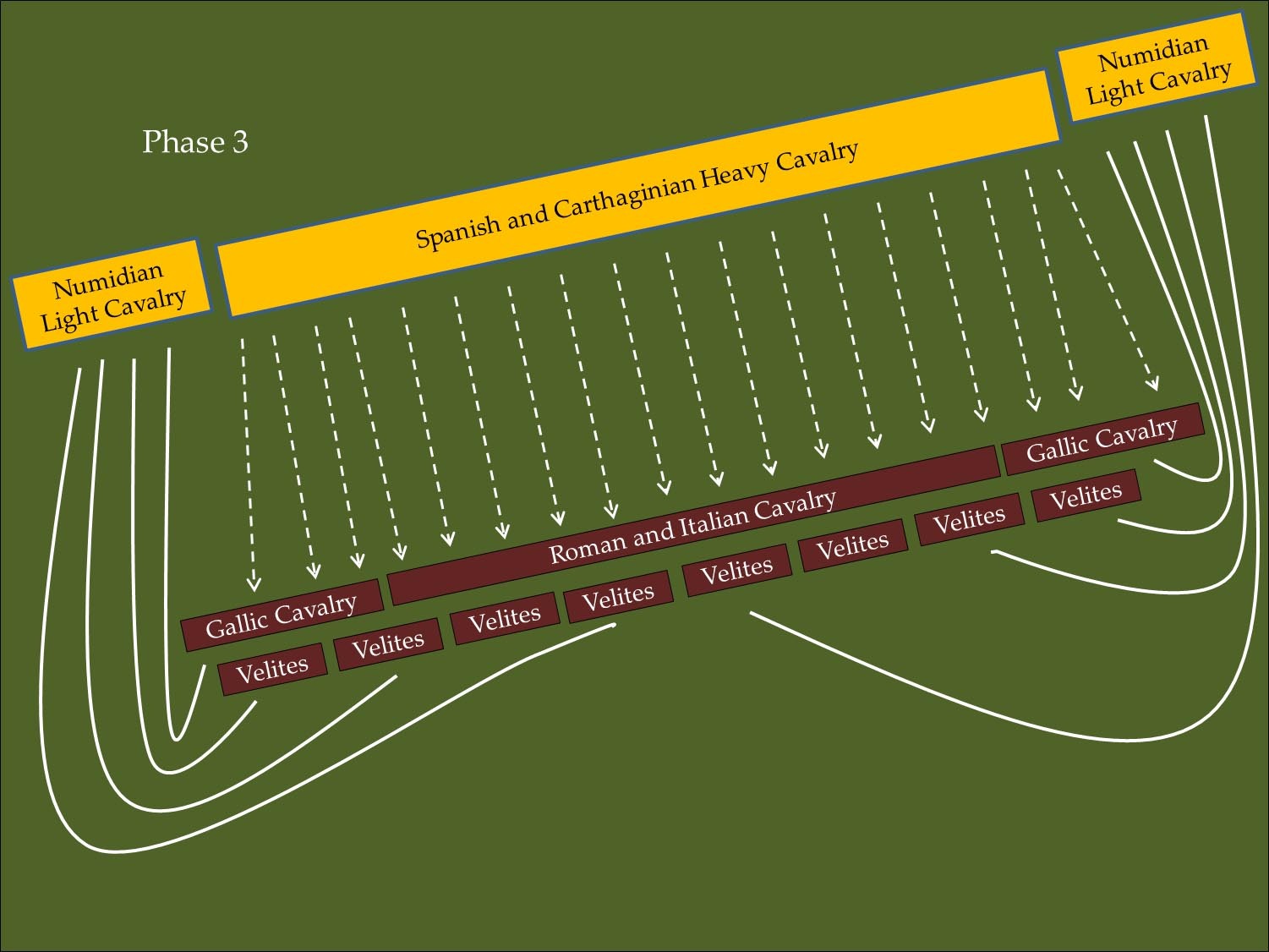

As the first Roman line advanced, Hannibal ordered his heavy cavalry to charge the velites and disrupt their attack. The velites retreated behind the Roman second line. Hannibal’s heavy cavalry slammed into the Roman line. In the meantime, his Numidian light cavalry circled around and hit the velites from behind.

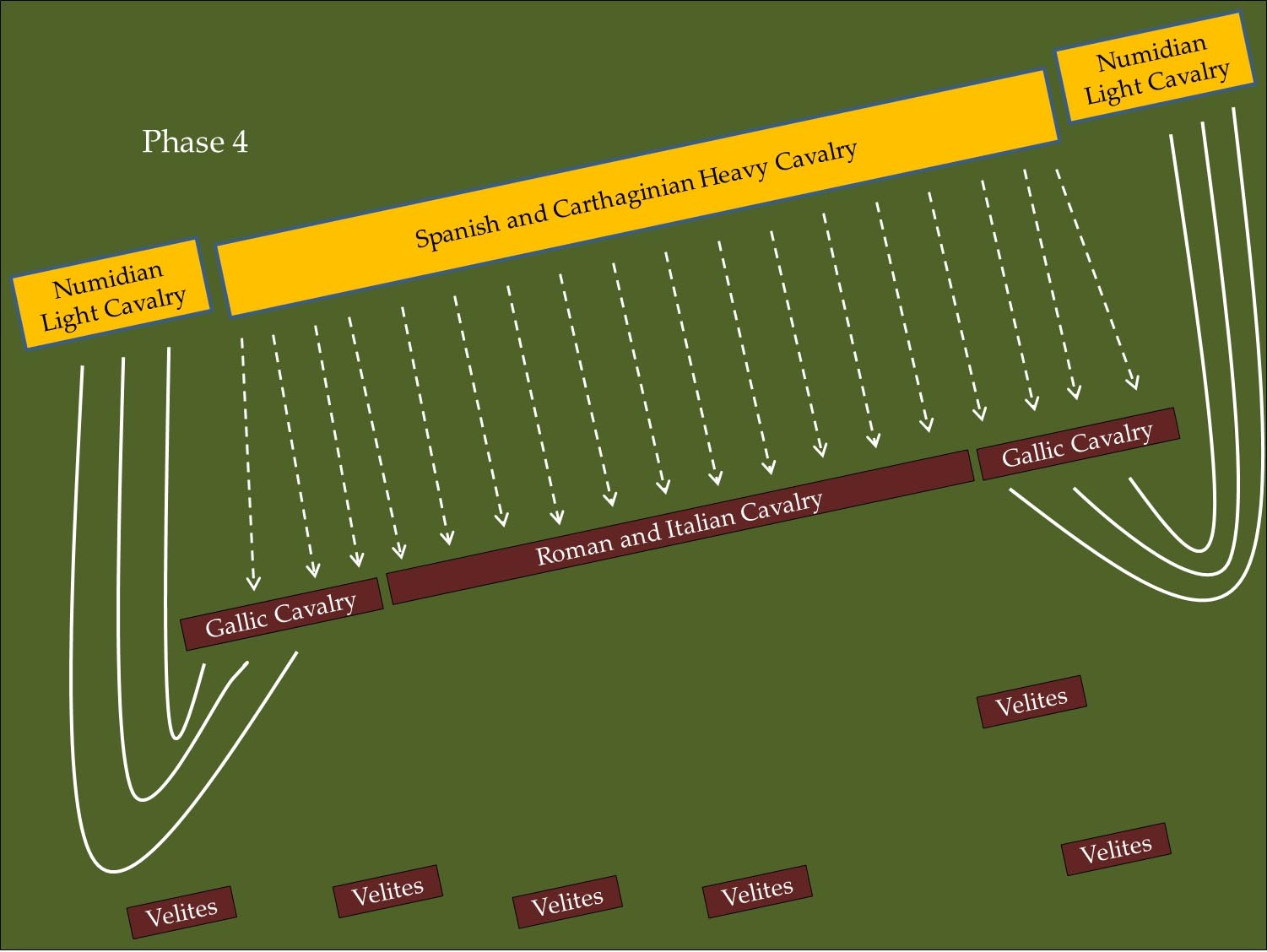

Ticinus—Phase 4

Hannibal’s Numidian Cavalry scattered the velites and struck the Roman wings from behind. Until that moment, the Roman cavalry had maintained its formation. Now the Roman force began to disintegrate. The only orderly withdrawal was by the small company surrounding a badly wounded Scipio.

Battle of Trebia

The battle of Ticinus was a prelude to a full scale battle at the Trebia River several weeks later. Ticinus was primarily a cavalry engagement in which the Carthaginians held the field but, according to Polybius, may have lost more men. Furthermore, Scipio, the commander, was seriously wounded. After the engagement, both armies maneuvered in an attempt to gain or maintain strategic advantage; Scipio getting his army to safety while keeping an eye on Hannibal, maintaining a presence to support his Gallic allies (Ananes and Cenomani) and potentially threatening the Insubres; Hannibal threatening Placentia to keep the Roman force fixed at that place while demonstrating to the Gallic tribes that his army had the initiative and that an alliance with Carthage against Rome was a promising proposition. In the meantime, Tiberius Sempronius Longus along with his African invasion force was redeployed to Cisalpine Gaul in order to join Scipio and his Praetorian force and contain, then destroy, the Carthaginian army. In the meantime, Hannibal took Clastidium, a Roman supply depot, by means of a bribe. Thus his army, now swelled by Gallic reinforcements to 90,000 men, was well supplied. Even though Hannibal occupied a central position that would allow him to prevent a Scipio-Longus linkup, Longus somehow evaded him.

As he sat astride the road between Scipio and the arriving Longus, Hannibal’s men plundered a local Gallic tribe (Ananes) that had stayed loyal to Rome. Scipio had left his camp near Placentia and had planted himself in their midst in an attempt to provide them support against the Carthaginians and their allies. Scipio’s camp was on broken ground that was less advantageous to cavalry than the plain around Placentia. Another Gallic tribe, the Cenomani, also remained faithful to Rome and hostile to the Insubres.

Despite Hannibal’s central position, Longus and Scipio managed to join forces (the two armies staying in separate camps) but Scipio was still recovering from his wound suffered at Ticinus. This left Longus in charge. Hannibal, never one to rest and do nothing, had a force of infantry and cavalry plundering the farms of Gallic tribes that were negotiating simultaneously with the Carthaginians and Romans. Longus’ reconnaissance party caught these raiders and dispersed them, causing heavy losses. This cheap victory left Longus thinking that his cavalry and infantry were superior to that of Hannibal.

Scipio tried to persuade Longus not to engage Hannibal before he had trained up his raw recruits. Longus, shortly after his success against Hannibal’s raiding party and being of an impetuous nature, was eager to face the enemy. Hannibal, apparently knowing this, teased Longus into a battle at the place and time of his choosing. He had a force of Numidians raid the Roman camp and taunt the Roman sentries. It was early morning, the Numidians had eaten breakfast sooner than usual, but the Roman troops had not yet had their breakfast nor were they prepared for battle. Nevertheless, Longus deployed his cavalry and light infantry and chased off the Numidian cavalry. He then deployed his entire army and chased the Numidians across the Trebia River. It was late December and it was sleeting. The Romans plunged into the freezing cold Trebia which was in places chest deep. By the time they reached the other shore, they could barely feel their arms or hold their weapons.

Trebia River

The Trebia is a fordable river. In the winter, however, it can be chest deep and extremely cold. Roman troops had to cross the freezing river to face the Carthaginian army on the other side.

Photo available at https://www.tripmondo.com/italy/

emilia-romagna/provincia-di-piacenza/casaliggio/.

Accessed 05/08/18.

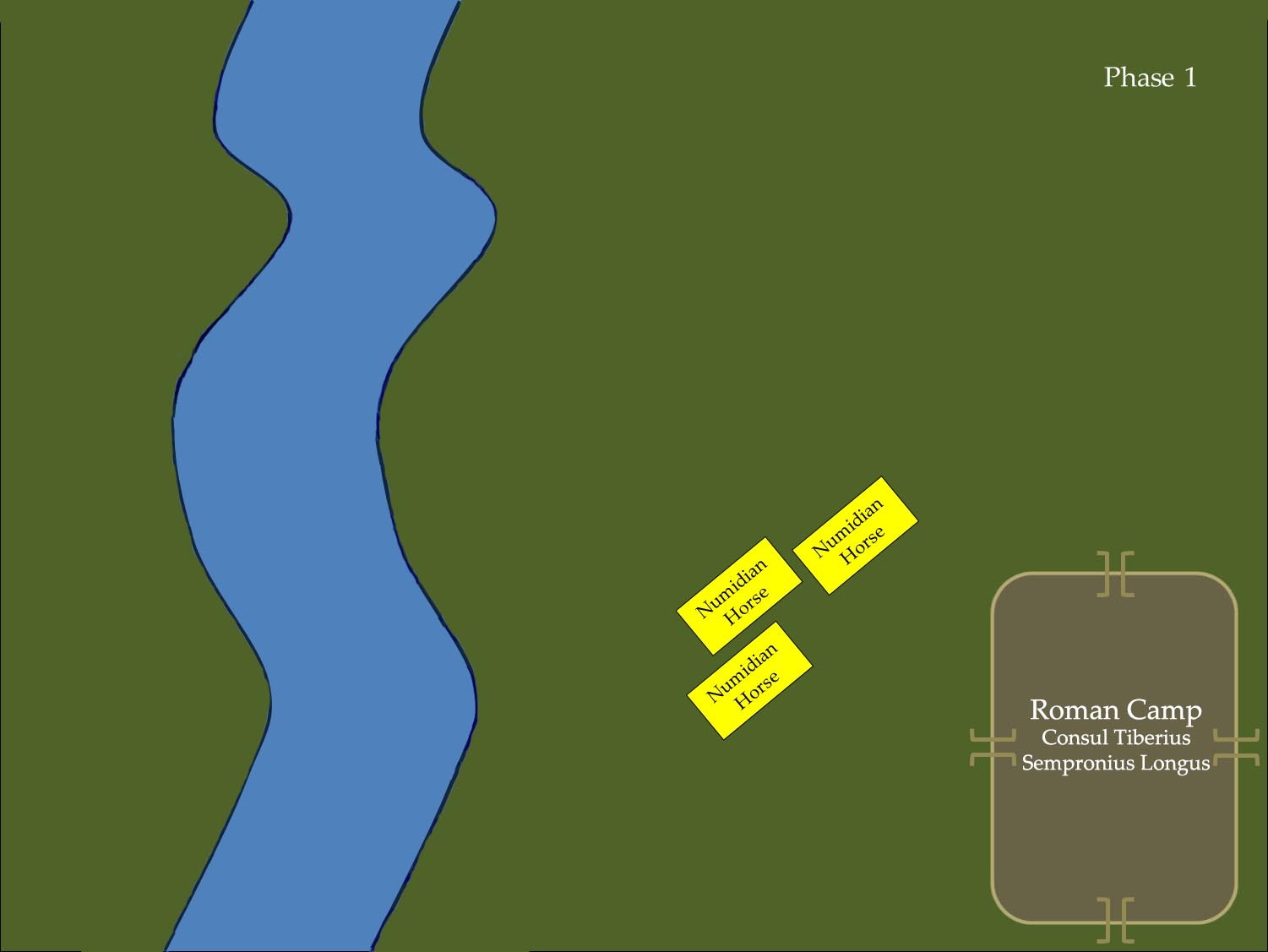

Battle of Trebia—Phase 1

The Numidians, after eating breakfast, rode across the Trebia River and harassed the soldiers in the Roman camp. Their orders were to draw the Romans out and tempt them into a full scale battle on the other side of the river.

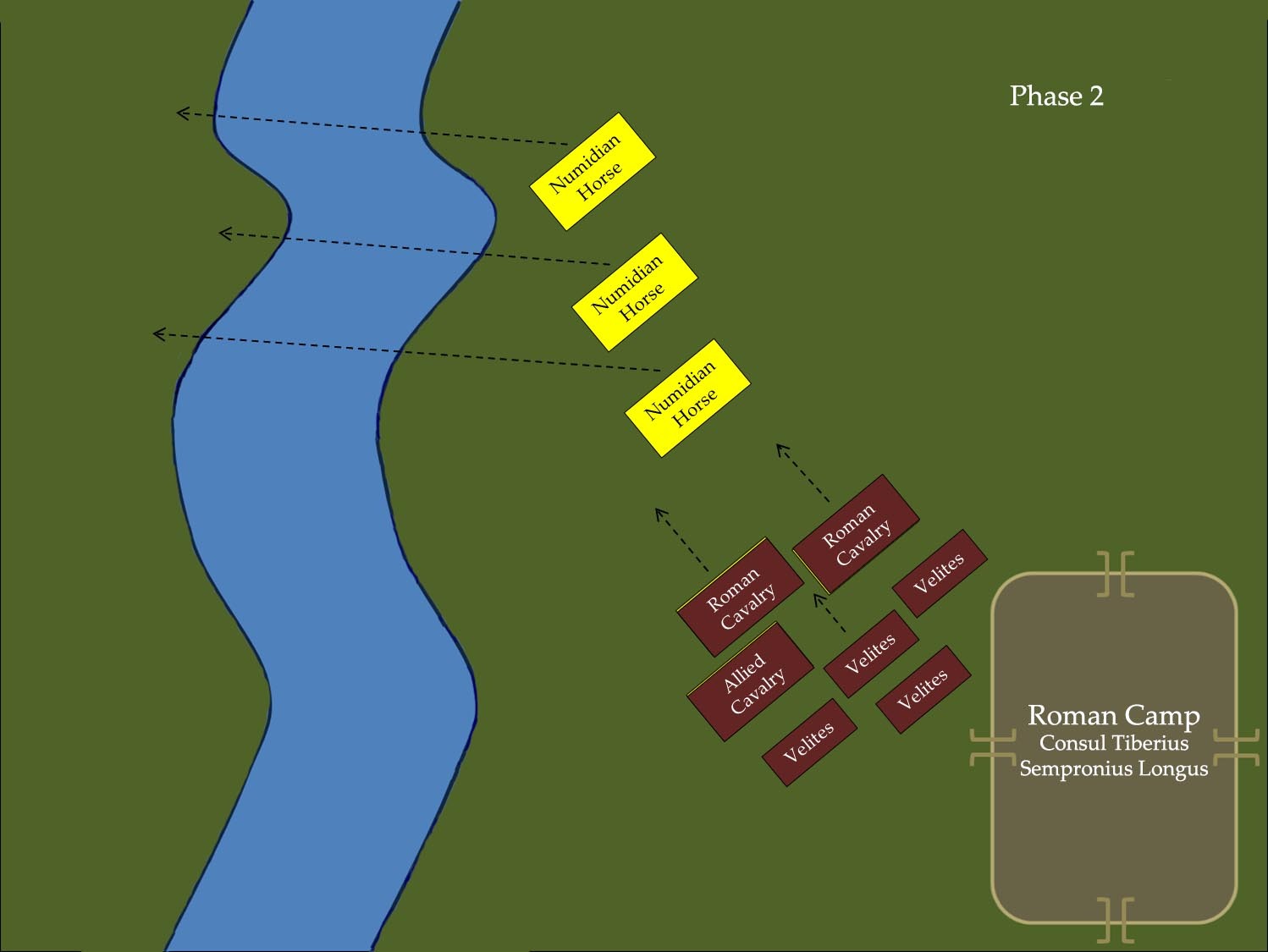

Battle of Trebia—Phase 2

The Numidians harassed the Romans until Longus sent his cavalry accompanied by his light infantry (velites) to chase them off. The Numidians recrossed the Trebia River and the Romans followed.

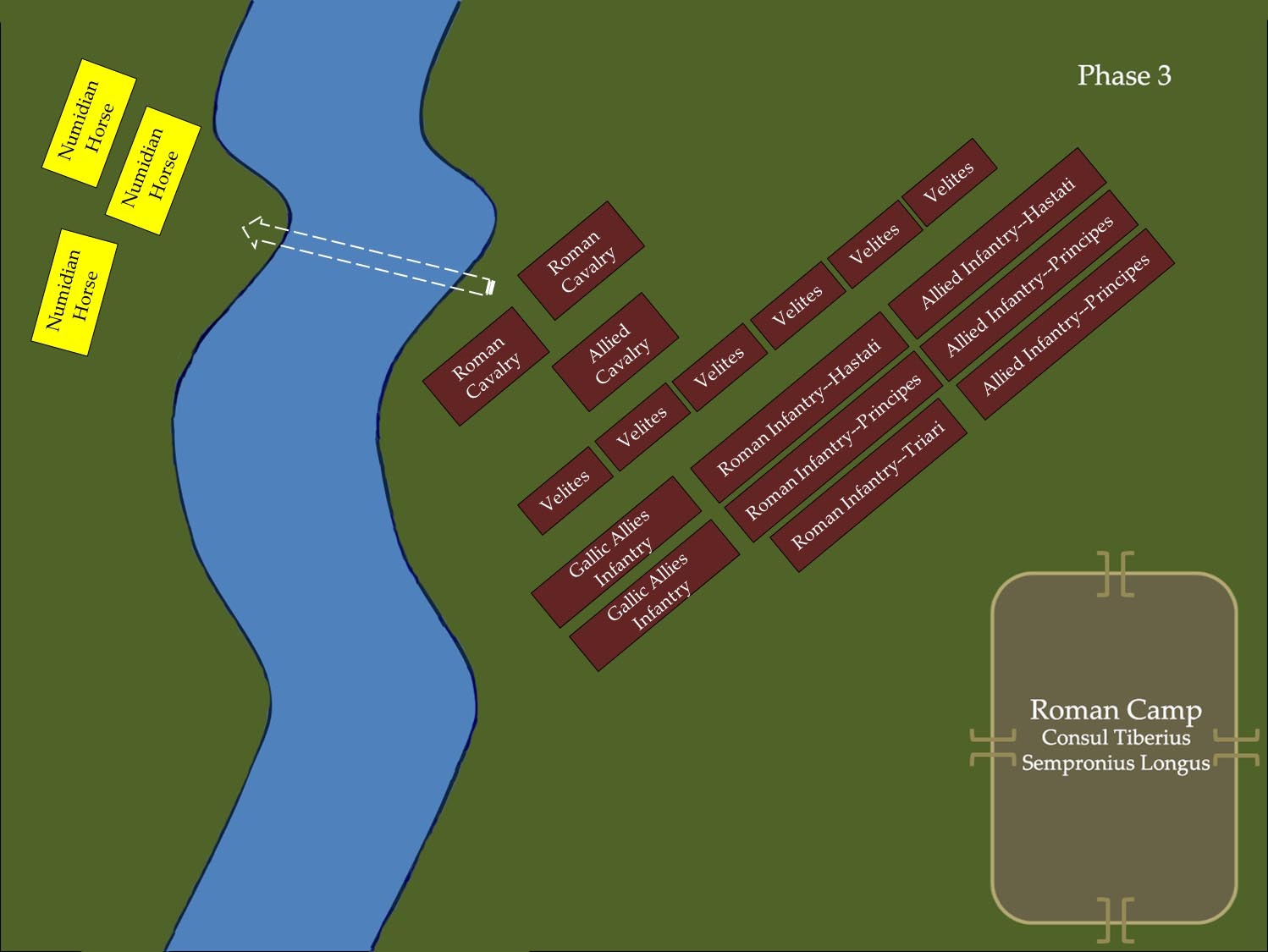

Battle of Trebia—Phase 3

Longus had his entire army assemble in battle formation and proceed to cross the freezing Trebia River. None of his troops had had breakfast or time to prepare themselves for the coming battle.

Nevertheless, the Romans resumed their formation in good order and began an advance up the plain toward the Carthaginian army.

While Hannibal was waiting for the Romans, his men had eaten and rubbed oil on their skin to protect against the cold. Furthermore, Hannibal had, under the command of his brother Hanno, a strike force of combined infantry and cavalry hide in the ravines along the river. The advancing Romans did not see them.

Hannibal’s army waited on rising ground for the enemy. Hannibal had deployed his Gallic allies in the center of his line. To the left and right of the Gauls were his Iberians and Libyan spearmen, then came the elephants on each side of the infantry and on the wings his cavalry.

As the Roman lines approached, they were preceded by 6,000 velites. Behind them were 10,000 Roman and 20,000 allied Italian heavy infantry arranged in the 3 lines (triplex acies). To the right marched Gallic infantry. On the wings rode 4,000 Roman and allied cavalry.

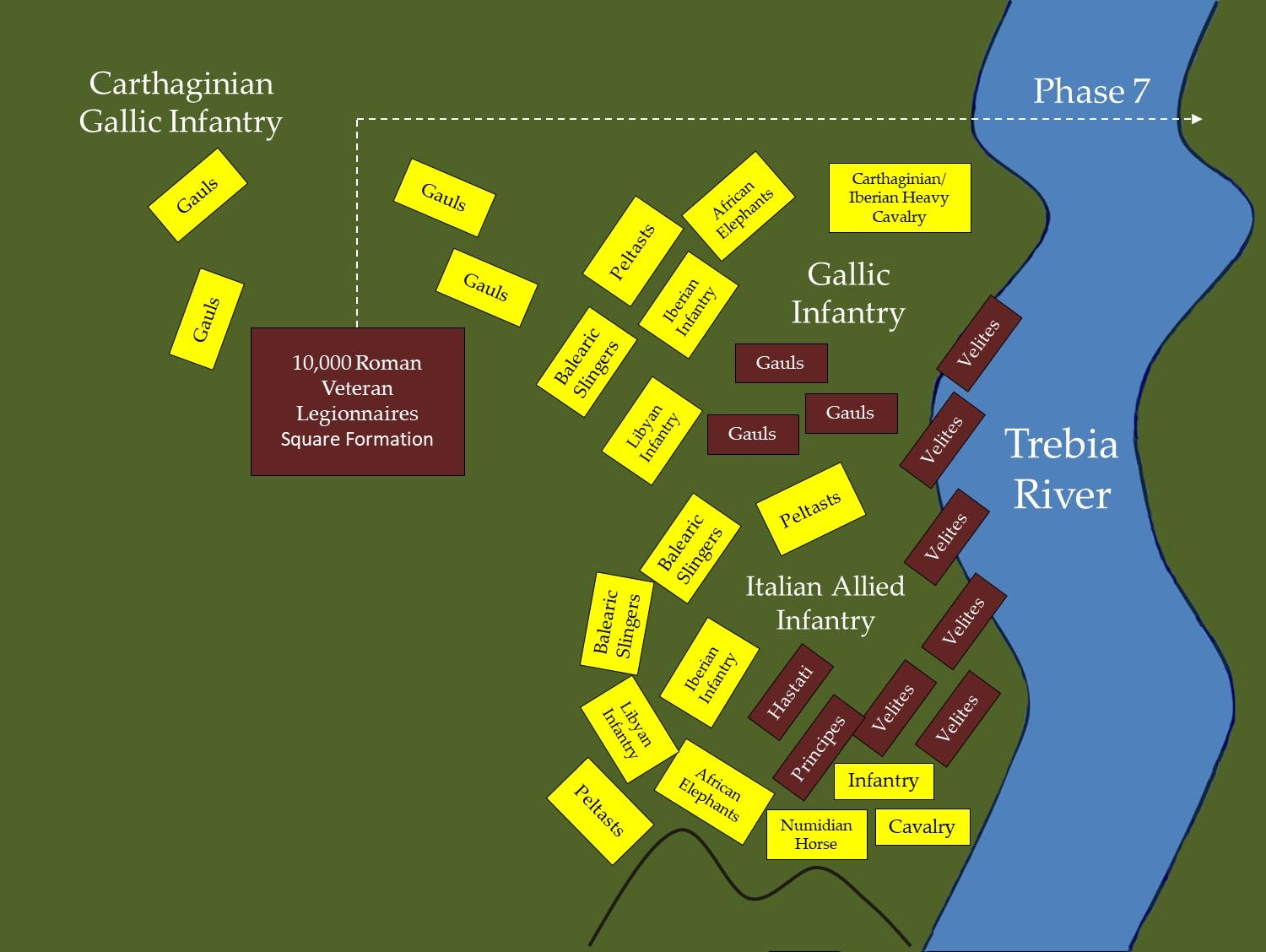

The Battle of Trebia—Phase 4

The Roman army arranged itself with great discipline after it crossed the Trebia River. The Roman veterans were in the center, the Italian allies (mostly raw recruits) on the left and Gallic allies on the right. Roman and Italian cavalry was on the wings.

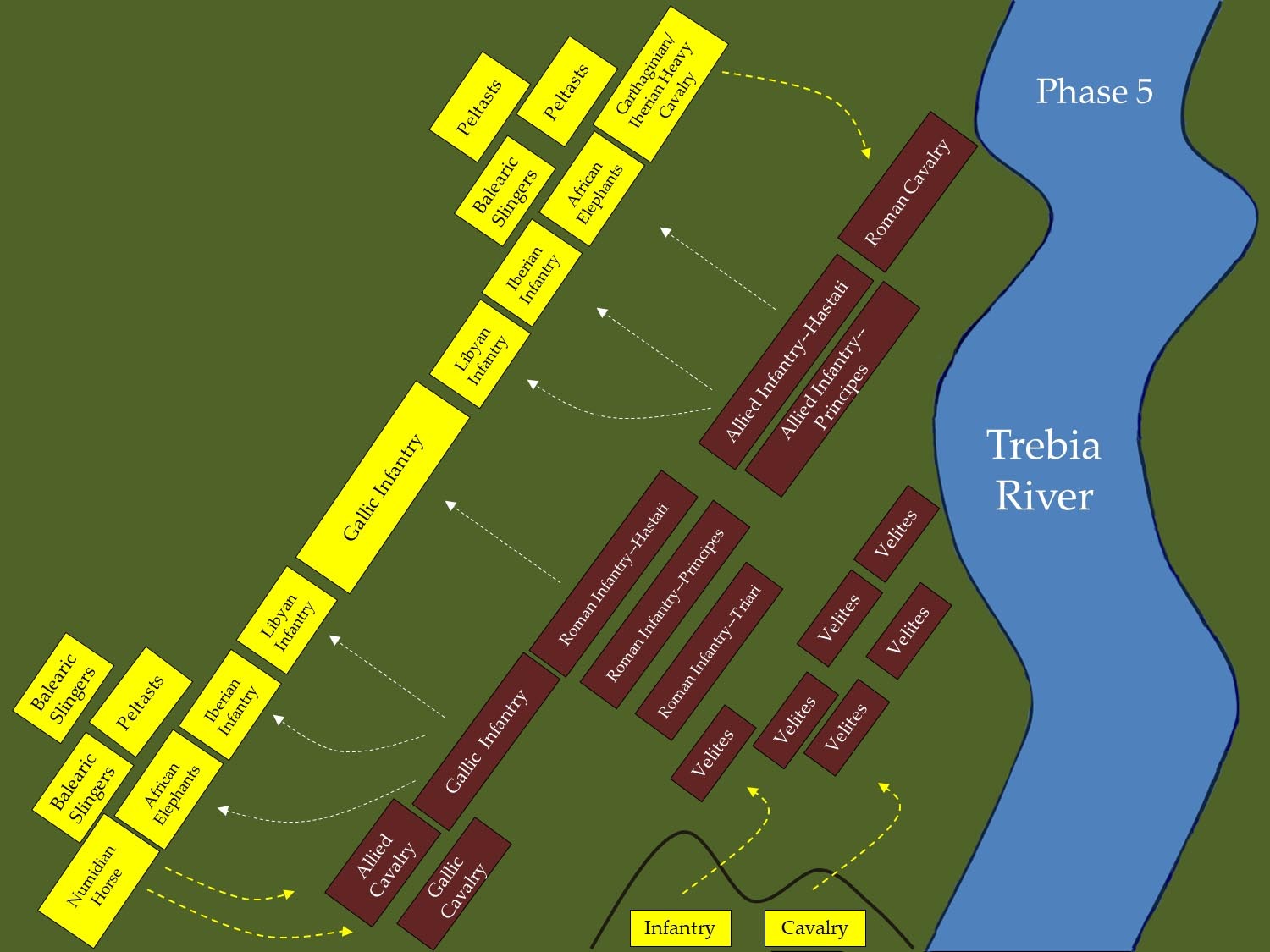

The Battle Trebia—Phase 5

As the Romans approached the waiting Carthaginian line, they were preceded by 7,000 skirmishers (velites). These were chased behind their heavy infantry by the Carthaginian peltasts and by the lethal Balearic slingers who then deployed around the elephants. Hannibal’s cavalry drove the outclassed Roman and allied horse off the field.

The battle hardened Carthaginian peltasts and Balearic slingers caused the Roman velites to take shelter behind their heavy infantry. They then redeployed to the spaces around the elephants. The Carthaginian cavalry (10,000 Numidians, Carthaginians, Iberians and Gauls) drove the Roman and Italian cavalry from the field then returned to hit the left and right wings of the Roman army in the flank as they fought the Iberian and Libyan infantry and skirmishing troops in front of them. The elephants were moved to the left wing to face the Roman Gallic allies where they did much damage. In the meantime, Mago and his handpicked 2,000 men emerged from the ravines where they were hiding and hit the Roman rear.

The Battle Trebia—Phase 6

The Iberian and Libyan infantry on either side of the Carthaginian Gallic center took on the left and right wings of the Roman army. In the meantime, the Hannibalic cavalry returned to the field and hit the Roman allied and Gallic infantry in the flank. At the same time, Mago’s ambush force of 2,000 men hit the Romans in the rear.

The Battle Trebia—Phase 7

The wings of the Roman army disintegrated. A great slaughter began at the river. The number of Longus’ men killed amounted to 30,000. In the meantime, the Roman center, under direct command of Longus, formed a square (or circle?) and cut their way through the Gallic center, inflicting grievous losses. These legions maintained their formation, recrossed the Trebia and reached their camp in safety.

The wings of the Roman army disintegrated. Only the Roman center, approximately 10,000 Roman legionnaires, kept their formation (forming a square) and took a heavy toll on the Gauls facing them. After cutting their way through the Carthaginian center, they wheeled right, then right again, recrossed the Trebia River and reached their camp in safety. The battle was a strategic victory for Hannibal. It left him in control of the Gallic countryside. It put the Romans back on their heels. It convinced the Gauls that supporting the Carthaginian cause was the best way to keep their independence from Rome.

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. 3rd Edition. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891. This edition copyright © 1891 The Riverside Press. Cambridge Mass. USA. Pages 252.

Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire (Classics). Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert Selected with an Introduction by F. W. Walbank. Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition. Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

The winter of 218-217 BC

After the battle, Scipio gave up his camp and returned to Placentia. There he took over command of Longus’ remaining troops as well as his own forces. Longus returned to Rome. Hannibal controlled the entire countryside and raided Rome’s allies for supplies (probably the Ananes and Cenomani). Many of the elephants died from the cold. Hannibal knew he had superior cavalry but he also knew that the Romans had formidable infantry, and when well trained, capable of tactical discipline, initiative and flexibility on the battlefield. He also knew the spring would bring fresh Roman legions to the north.

The Roman troops in Placentia were being supplied by boats up the Po River. The town of Emporion enabled the Romans to maintain an open supply line. Hannibal tried to take the place, but the Romans quickly came to its relief. Hannibal was slightly wounded during the skirmish. Later, Hannibal was able to take the town of Victumviae which lay astride his lines of communications with Liguria. The inhabitants fielded a force of 35,000 men which Hannibal crushed. The town surrendered. Hannibal put all Roman soldiers to the sword and gave the town up to plunder. With the advent of severe weather, Hannibal took his army into winter quarters. However, February brought a mild spell during which Hannibal attempted another mountain crossing, this time over the Apennines into Etruria. The effort was a complete failure, with great loss of men, elephants and material. Chastised by mother-nature, Hannibal returned his army to within 10 miles of Placentia.

In the meantime, Sempronius returned from Rome and fought a minor engagement with Hannibal, which was a draw. He and Scipio then withdrew from Placentia, leaving a garrison behind. Scipio retired to Ariminum and Longus to Luca. They thus covered two lines of access to central Italy, Sempronius in the west and Scipio to the east.

Hannibal was left in control of Cisalpine Gaul. Furthermore, he consolidated his relations with the Ligurians, receiving from them Roman hostages. His army wintered with the Ligurians.

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. 3rd Edition. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891. This edition copyright © 1891 The Riverside Press. Cambridge Mass. USA. Pages 269-274.

218 BC, autumn

Cnaeus Cornelius Scipio in Spain

While Hannibal was consolidating his control over Cisalpine Gaul, Scipio (Africanus’ uncle and the wounded Publius Cornelius Scipio’s brother) had sailed from Massilia and landed in Emporion (Catalonia) where he undid much of the work of Hannibal. Using Emporion as his base, Cnaeus Cornelius Scipio sailed down Spanish coast winning over locals. He commanded 4 legions (2 Roman, 2 allied) and a fleet of 60 quinqueremes. He met Hanno and his army of 10,000 infantry, 1,000 cavalry at Cissa, near the city of Tarraco, and beat him, taking him prisoner. He captured the Carthaginian camp with its baggage train and the Spanish chieftain Indibilis as well. Hasdrubal, however, marched across the Ebro and won some minor victories over the Romans. Hasdrubal then withdrew to Qart Hadasht for the winter while Scipio went into winter quarters near Tarraco (Tarragona).

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891. This edition copyright © 2012 Tales End Press. Pages 270-275.

217 BC

The Marshes of the Arnus River

Roman Politics and Mobilization

In the spring of 217 BC, the Romans and Carthaginians sprang into action. Two new consuls were elected; Gaius Flaminius and Gnaeus Servilius Geminus. Flaminius raised another consular army (two legions accompanied by two alae*). Servilius stayed in Rome to raise more troops and ensure logistical support for the newly raised forces.

Flaminius concentrated his troops at Arretium.

*Two alae are the Italian allied equivalent to two Roman legions. 1 ala = 1 Legion.

Strategic Considerations

- Romans wanted to overwhelm Hannibal with numbers, so they raised two new consular armies; the Romans now had 100,000 men under arms.

- They wanted to keep Hannibal out of central Italy, so they maintained an army at Luca and at Ariminum.

- Hannibal wanted to reach central Italy (Etruria, Umbria and Campania) and separate her allies from Rome.

- Hannibal’s strategy was to maintain a constant offensive.

- Hannibal had to keep his Gallic allies happy which meant providing opportunities for plunder in central Italy.

- Hannibal had logistical considerations; he had a large army to feed and having them supported by the economy of his allies would have been a burden and would have soured relations over the long run.

Hannibal Leaves Liguria, Heads South and Threatens Rome

Hannibal Leaves Liguria Heading South, Turns East at Luca into the Arnus Marshes, Crosses the Arnus River near Faesulae and Begins Devastating Etruria While Strategically Placing Himself between Flaminius and Rome.

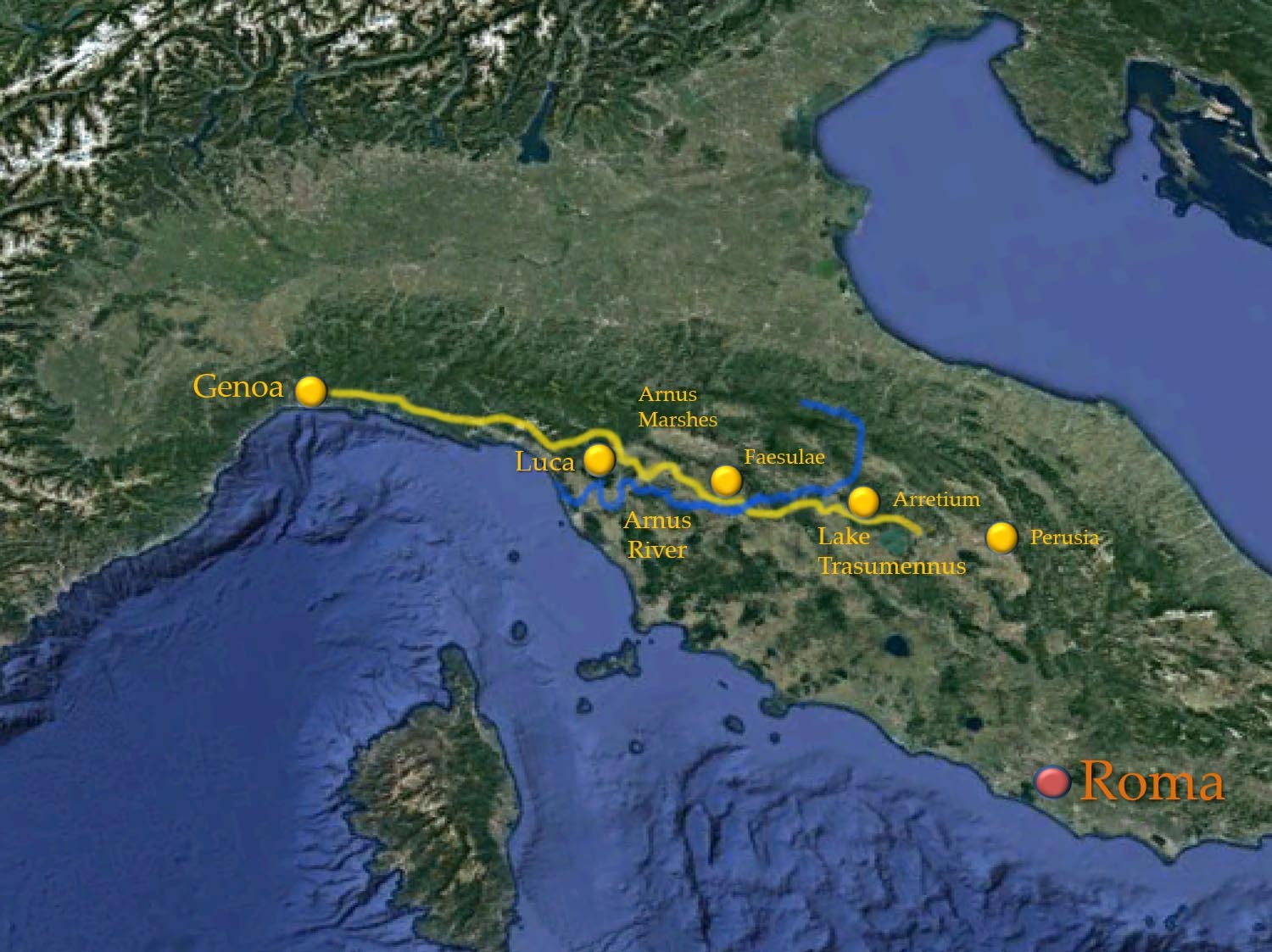

Hannibal wintered his army in Liguria. With the arrival of spring, he moved to Genoa. After marching along the coastal road from Genoa, Hannibal turned east above the town of Luca. There he was confronted by the marshlands of the Arnus River. That year (spring, 217 BC), was a particularly wet year and the marshes would have been even more difficult to traverse than usual. It was almost as difficult as crossing the Alps. Hannibal’s army took four days and three nights without rest to get through. Hannibal rode his sole remaining elephant. He lost sight in one eye due to inflammation. The Gallic contingent suffered the most. The army reached Faesulae (Fiesole) near modern Florence where they acquired provisions. They then crossed the Arnus and began to devastate the Etruscan countryside. Strategically, Hannibal had flanked Flaminius, who was still at Arretium (Arezzo), to his west and, as he headed south, placed himself between the Consular army and the city of Rome.

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. 3rd Edition. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891. This edition copyright © 1891 The Riverside Press. Cambridge Mass. USA. Pages 278-298.

Hannibal’s March into Etruria and Lake Trasumennus

In the spring of 217 BC, Hannibal left winter quarters in Liguria, passed through Genoa and headed south toward the Arnus River. He turned east at Luca and slogged through the Arnus Marshes. He crossed the Arnus River near Faesulae and began pillaging the Etruscan countryside. As he marched southeast toward Perusia, Hannibal interposed himself between Flaminius and Rome. Flaminius was compelled to follow.

Battle of Lake Trasumennus

As Hannibal went along pillaging Etruscan territory, he kept heading south. Flaminius was presented with a conundrum. Militarily, he was better off staying in camp and waiting for support from his fellow consul. His allies, the Etruscans, however, were distressed by the damage being done to their land. Furthermore, there was pressure from the capital to bring Hannibal to battle and destroy his army. So there were strategic as well as political pressures to consider. But it was Hannibal’s interposition between Flaminius and the city of Rome that galvanized Flaminius into action. As Hannibal headed toward Perusia, Flaminius felt compelled to follow.

Polybius and Livy have both described Hannibal as a wily general. Although personally brave and strategically and tactically bold, he preferred to win a victory through misdirection and surprise rather than brute force. Thus it was at Lake Trasumennus.

As Hannibal marched toward Perusia (Perugia), he entered a valley that lay on the northeastern shore of Lake Trasumennus. It was bracketed by a narrow defile at the entrance and at the exit. In between was a plain bordered on one side by the lake and on the other by elevated ground. He placed his camp near the exit. Flaminius, a day’s march behind, placed his camp near the entrance to the valley. Neither Livy nor Polybius provides details about the ensuing battle. But the author TA Dodge, himself a military man who covered the actual ground on which the battle was fought, draws upon his experience as a lieutenant-colonel with the Union Army during the American Civil War and upon his imagination to fill in the details of the battle at the lake.

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. 3rd Edition. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891. This edition copyright © 1891 The Riverside Press. Cambridge Mass. USA. Pages 303-314.

217 BC (summer, autumn and winter)

After Trasumennus, Hannibal spent the rest of the year in Apulia, foraging for supplies, trying to bring a newly raised Roman army to battle and talking with Rome’s non-Latin allies.

The disaster at Trasumennus finally convinced the Romans that their system of raising two consular armies a year along with an offensive strategy of bringing their foe to battle as soon as possible was not working with a gifted military leader like Hannibal. Consequently, they elected as dictator the elderly and cautious former consul Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus. Because the Romans had lost about 70,000 men in 3 battles—Ticinus, Trebia and Trasumennus—versus the Carthaginian, Fabius introduced a strategy of non-engagement in set-piece battles. Instead, the Roman army would shadow Hannibal as he moved through the Italian countryside, staying to the hill country, picking off his foraging parties. This was an intelligent strategy because it denied Hannibal his two greatest strengths; 1) his superior set-piece battle tactics, and 2) the advantage of his superior cavalry. It also put pressure on Hannibal’s logistics and upon his political objective, breaking up the Roman Confederation. Fabius’ delaying strategy, however, was not without its weaknesses. For the allies whose lands were being devastated by Carthaginian fire and sword, it was difficult to see the bigger strategic picture when the pain was so immediate. For Fabius’ opposition in the Senate, his strategy worked against the very nature of the Roman approach to war; to always take the offensive.

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. 3rd Edition. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company. © 1891. The Riverside Press. Cambridge Mass. USA. Pages 315-380.

PHASE III

The Darkest Hour is Just Before Dawn

216 BC

Roman Strategy

Hannibal’s invasion of Italy in 218 BC stole the military initiative from Rome. Initially, the Senate had sent a Consular army to Massalia under Publius Cornelius Scipio and his brother Cnaeus Cornelius Scipio in preparation for an invasion of Spain. Another Consular army under the command of Tiberius Sempronius Longus was deployed to Sicily as a preliminary to the invasion of the Carthaginian homeland. However, Hannibal’s 1,200 mile march to Italy forced the Romans to redeploy their African invasion force to Cisalpine Gaul and the elder Scipio to Gaul as well. Although the Consular army which missed Hannibal at Massalia deployed to Spain under command of Scipio’s brother, Rome was forced to raise another army and confront the Carthaginians in Gaul. There the Romans were soundly defeated at Trebia and the following year, 217 BC, in Umbria at Lake Trasumennus.

In 216 BC, Publius Cornelius Scipio was sufficiently recovered from the wound sustained at the battle of Ticinus to join his brother in Spain with an additional 8,000 troops and a small fleet. Their objectives were to recruit Spanish allies, destroy the Carthaginian armies and deny Hannibal the mineral and manpower resources of Spain. Lucius Postumius Albinus was sent to Cisalpine Gaul with a proconsular army to stifle support for Hannibal. The primary objective was the destruction of Hannibal’s army in Apulia.

Roman Strategic Objectives for 216 BC

Publius Cornelius Scipio recovers from his wound at Ticinus and joins his brother in Spain. Their objective is to deny the Carthaginians the mineral and manpower resources of the Iberian Peninsula. Lucius Postumius Albinus marches with a consular army to Gaul in an attempt to separate the Gauls from Hannibal. A third force under Varro and Paulus marches to Apulia with the intent to destroy Hannibal’s army.

Battle of Cannae

The Roman army commanded by the Consuls Lucius Aemilius Paulus and Gaius Terentius Varro was destroyed as a fighting force by Hannibal and the Carthaginians. This was the nadir of Roman fortunes during the Second Punic war and the defeat had strategic implications. Shortly thereafter, Capua and some other southern Italian tribes and cities joined the Carthaginian side.

There is debate among scholars as to the size of the Roman army at Cannae. Some historians place the number of legions at 8 with a matching number of alae (allied legions). This yields a number of 86,000 men. Other historians think this number is too large and estimate the number at 50,000. Whichever number we accept, it is generally agreed that the Romans and their Italian allies outnumbered the Carthaginians.

Livy estimates that 40,000 Romans and Roman allies perished at Cannae. Among them Aemilius Paulus the consul, 80 senators, 30 of whom had served as consul, praetor or aedile.

These efforts paid dividends, with the Arpani, Brutti, and the city of Capua leaving the Roman alliance. Also, the democrats in the city of Tarentum brought that city into the Carthaginian fold, but they weren’t able to capture the citadel and harbor. With the Gauls in revolt in the north, this was the nadir of Roman fortunes.

Hannibal after Cannae

This drawing (by Zygmunt Michalski) is based on a statue by Sebastien Slodtz (1704) that stands at the Jardin de Tuileries in Paris. It represents Hannibal after his victory at Cannae. His right hand rests upon an inverted legionary eagle, sacred to a Roman legion. His left hand fingers some of the iron rings in a vase full of them. These were worn only by the Roman upper classes, so, presumably, this vase represents the Roman elite that perished at Cannae. Hannibal’s left foot stands on another legionary eagle and a bundle of rods (fasces), symbol of a Roman magistrate’s authority. His right foot is supported by a shield, below which are a gladius (Iberian style sword) and a vexillum (a standard that could represent a particular body of troops within a legion or the entire legion itself).

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. 3rd Edition. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company. © 1891. The Riverside Press. Cambridge Mass. USA. Pages 315-380.

Livius, T. The History of Rome, Books 9-to-26. Trans. D. Spillman. London. Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden. 1853. John Childs and Son, Bungay. Project Gutenberg. Produced by Ted Garvin, Taavi Kalju and the Online Distributed Proofreading team at http://www.pgdp,net. November 6, 2006. EBook #19725. Page 123

O’Connell RL, The Ghosts of Cannae. Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. New York. ©2010. Kindle Edition.

Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire. Ian Scott-Kilvert (Trans.), 1979. Penguin Books, Ltd. London. pgs. 134-138.

Spain, 215 BC-211 BC

Hasdrubal Barca was defeated at the battle of Dertosa which prevented him from reinforcing Hannibal in Italy after Cannae. Carthage sent reinforcements to Spain under two generals, Mago Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco, who fought the Scipiones in 215, 214, and 213 BC with no favorable outcome. In 213, Syphax, a Numidian King, rebelled against Carthage and Hasdrubal Barca was obliged to cross over to Africa in order to quell the uprising. Syphax and his army were crushed and Syphax was forced into exile. Hasdrubal returned to Spain in 212 BC along with Massinissa, a Numidian prince, and 3,000 Numidian cavalry. Hasdrubal, along with Mago Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco, was able to defeat the Romans at the Battle of the Upper Baetis. Both Roman generals, Publius Cornelius Scipio and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus were slain and the remnant of the Roman army was forced to retreat north of the Ebro River.

Shortly thereafter, Publius Cornelius Scipio, now 25 years old, offered to take command of Roman forces in Iberia. This was fortuitous because no Roman commander wanted the job.

215 BC

The Battle for Campania

After Cannae, Marcellus, who was raising an army for the invasion of Africa, was recalled to Rome. Part of his army, approximately 1,500 men was redeployed to the city of Rome, while the rest of his forces followed him to the city of Suessula in Campania. He checked elements of Hannibal’s army from taking the city of Nola. This was a significant moral victory because it was the first bit of good news after the twin disasters of Cannae and Silva Litana (the Litana Forest where the Gauls ambushed and destroyed a Consular army) at the hands of the Carthaginians and the Gauls.

Capua along with several cities and tribes defected to the Carthaginian side. Hannibal’s army left a garrison in Capua over the winter. The Carthaginians took some secondary towns in Campania such as Casilinum (a few miles from Capua). They attempted to take the city of Nola but were repulsed by the Romans. The Romans tried to besiege Capua but Hannibal chased them off the first time. However, they were able to return and besiege the town again and by building an inward and outward line of circumvallation, were able to keep the Carthaginian relieving force at bay and continue the siege. Capua was starved into submission in 211 BC. The consequences for the city were dire; those members of the senate who didn’t commit suicide were flogged and beheaded. The city was stripped of its political rights (civitas sine suffragio) and put under a Roman Praefectus; approximately 50% of its land was confiscated and made ager publicus (public land) which could be allotted or sold to Roman citizens.

Illyria, Greece and Macedonia 215-206 BC

215 BC

Phillip V of Macedonia signs a treaty with Hannibal. He has interests in Illyria, a Roman protectorate, as well as in Greece proper. The Romans are able to keep Phillip busy by allying themselves with the Aetolian league.

214 BC

Roman Involvement in Greek Affairs

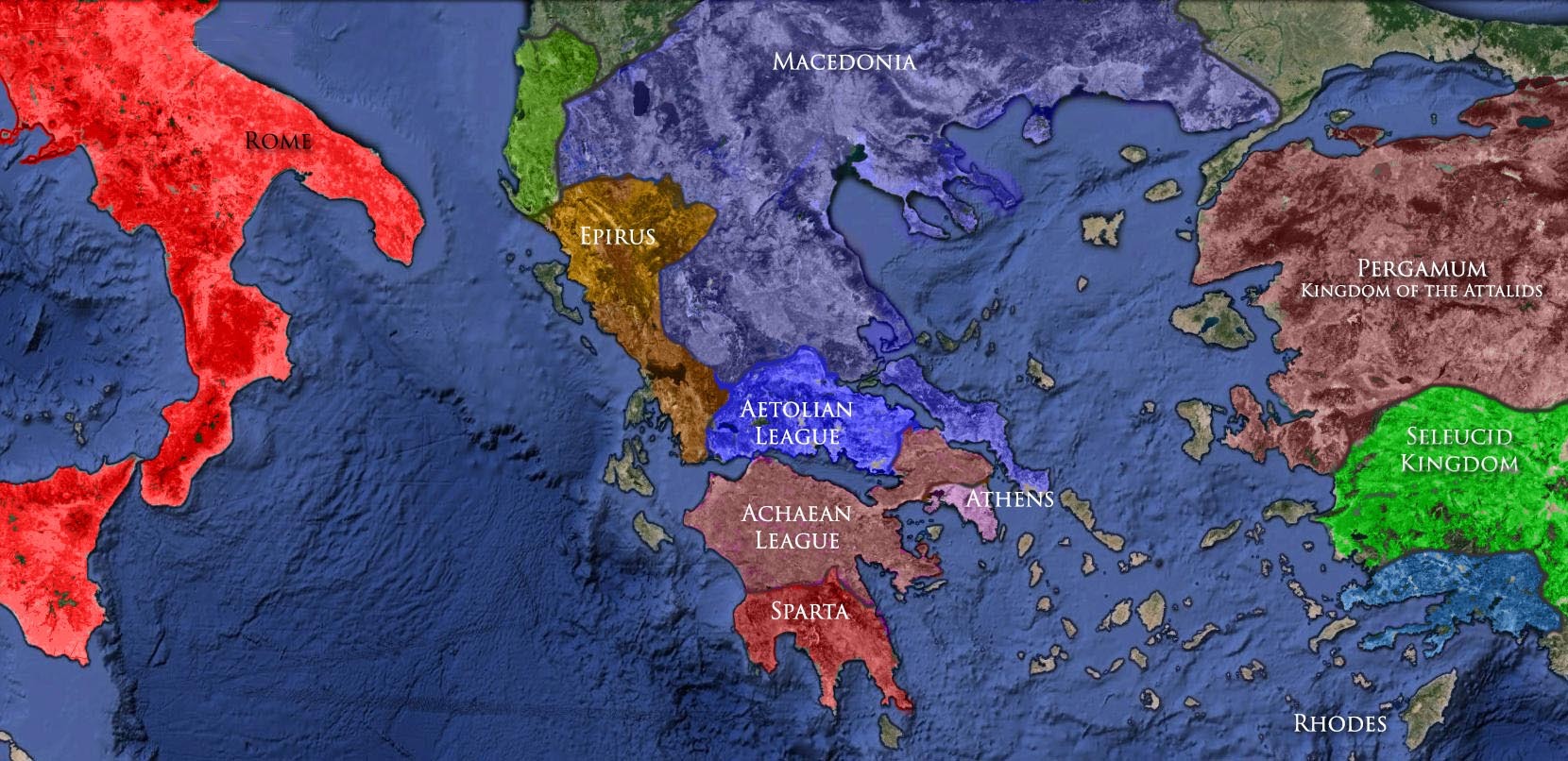

Rome was already involved in the Balkan Peninsula as the result of having to protect Roman shipping in the Adriatic and Ionian Seas from Illyrian predation. As a consequence, the Republic came into contact with the Hellenistic Kingdoms of Macedonia, Egypt, Epirus, Pergamum and Seleucids along with the Aeolian and Achaean Leagues, and the Independent Greek cities: Athens, Sparta, Rhodes, Cnidus, Chios, Mytilene, etc. The presentation of this cursory list is enough to suggest the complexity of the politics involved. These states were involved in a constant state of conflict with each other in ever changing alliances and political configurations. The major players, the successor states to Alexander the Great’s empire, the Kingdoms of Macedonia, Egypt and the Seleucids, would become embroiled in a conflict with Rome. The Kingdom of Macedonia was the first to be involved.

Hellenistic Kingdoms in Greece; 214 BC

The First Macedonian War

The war lasted from 214 BC to 205 BC. It involved Rome in alliance with the Aetolian League and the Attalids of Pergamum against Macedonia. Most of the fighting took place in Illyria, on the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea.

Belligerents in the first Macedonian War

Rome, Illyria, Macedonia, Pergamum, the Aetolian League, Achaean League, Elis, Messenia, Sparta. Rome was allied with the Aetolian League and Pergamum against Macedonia.

The Macedonian War began with an opportunistic move by Phillip V of Macedonia that took advantage of the Roman preoccupation with Carthage in order to extend his sphere of influence to the Illyrian coast. At the time, Phillip was counselled by Demetrius of Pharos, a former ally of Rome, who had been defeated by the Romans after he had broken the provisions of a treaty that forbade Illyrian pirate activity south of Lissus (A city on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. See map: Illyrian coast and the Lissus line). Demetrius hoped to recapture his lost kingdom after Phillip eliminated the Roman presence from the east coast of the Adriatic Sea.

The basis for the Macedonian war was a treaty between Carthage and Macedonia, which contained the following provisions:

- Mutual support and defense

- Be the enemy of your ally’s enemy

- Macedonian support for Carthage against Rome in exchange for control of Corcyra, Apollonia, Epidamnus, Dimale, Parthini and Atintania; also Demetrius of Pharos would have his lands restored to him.

However, the Republic was able to take Syracuse, which had gone over to Carthage after the death of its tyrant Hiero, after a difficult and lengthy siege. They were also able to bring Capua back into the fold after that city had allied itself with Hannibal. There were also some Roman successes in the field against the Carthaginians. Furthermore, Rome was able to muster a legion for operations in Illyria and Greece, and deploy a fleet for operations in the Adriatic under the command of Marcus Valerius Laevinus.

Hannibal’s strategic goal, the weakening of Rome, was never achieved because Phillip V of Macedonia had limited resources (he had no experienced fleet to fight along the Illyrian coast and thus lacked the confidence to fight aggressively.) and because of Roman diplomacy (an alliance with the Aetolians and the Attalids of Pergamum) which succeeded in tying Phillip down on the Greek mainland.

Consequently, there were no major battles fought in this war and the Romans were able to achieve their objective; the neutralization of Macedonia, leaving them free to concentrate on Carthage.

Livius, T. The History of Rome, Books 9-to-26. Trans. D. Spillman. London. Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden. 1853. John Childs and Son, Bungay. Project Gutenberg. Produced by Ted Garvin, Taavi Kalju and the Online Distributed Proofreading team at http://www.pgdp,net. November 6, 2006. EBook #19725. Page 295.

Mommsen, T. The History of Rome (Volumes 1-5). Translated by William Purdie Dickson. E-text prepared by David Ceponis. Project Gutenberg. Available at www.gutenberg.net. Accessed December 29, 2012. PDF Page 173.

Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire. Translated by Ian Scott Kilvert. Published by Penguin Putnam. New York, New York. 1979.

Sicily 215 BC

Carthaginians made a play for the island of Sicily by fomenting a revolt in Syracuse. Marcellus besieged the city, with no success. Archimedes’ engines saw to that. But Marcellus took the city by subterfuge when the Syracusans were celebrating a feast to Artemis.

Plunder from the city paid for the campaign and is said to have whetted the Roman appetite for Greek art.

PHASE IV

Rome Takes the Strategic Initiative

Spain, 211-206 BC

The younger Publius Cornelius Scipio was only 25 years old when he was given command over Roman forces in the Iberian theater. No other Roman wanted the job. His primary objective was to tie down the Carthaginian armies in Spain and prevent them from reinforcing Hannibal in Italy.

Scipio raised fresh troops and arrived in Spain with an army of 11,000 in 210 BC. He was based at Tarraco (Tarragona), north of the Ebro River. There he began integrating his fresh troops with the veterans of Gaius Lucius Marcius Septimus. This would yield an army of 28,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. Scipio spent the following year intensively training his army and collecting Iberian allies.

During the winter of 210 BC, Scipio’s intelligence told him that three Carthaginian armies were scattered throughout Spain. All of them were at least ten days march from the city of Qart Hadasht (Cartagena, New Carthage). In the spring of 209 BC, leaving behind 3,000 infantry and 500 cavalry, he marched his army south and besieged the Carthaginian capital. He took the city quickly before any of the Carthaginian armies could come to its rescue.

After slaughtering many of the inhabitants and enslaving many others, he put the survivors to work for the Roman state, manufacturing arms and training as rowers for his fleet. The commander of the city garrison and several members of the city council were sent to Rome. The Iberian hostages held by the Carthaginians at Qart Hadasht were freed and would be sent home if their tribes allied themselves with Rome. In the meantime, Scipio continued intensively training his troops. In the winter of 209-208 BC, he returned to Tarraco and mobilized all of his Iberian allies. In the spring of 208 BC, he marched south until he faced Hasdrubal Barca (Hannibal’s brother) at a place called Baecula. There, after a two-day standoff, he beat Hasdrubal with a frontal assault with his velites (light infantry) and a simultaneous attack on each flank by heavy infantry. Hasdrubal escaped with remnants of his army, his elephants and his baggage train, and headed for Italy to reinforce his brother Hannibal. Scipio did not pursue him.

Scipio was now left facing two Carthaginian armies. However, Carthage sent another army and a hefty war chest with Hanno to make up for the loss of troops under Hasdrubal Barca. Hanno joined up with Mago and had the intention of hiring significant numbers of Iberians. Scipio preempted this initiative by sending a force under Marcus Iunius Silanus that captured Hanno and crushed his army and sent Mago fleeing for his life.

Scipio Africanus and his Iberian Campaign 210 BC–206 BC

After his father and uncle were slain in Spain, the younger Scipio was appointed as commander for that theater of war. He managed to take the peninsula and convert it to Roman use in just five years.

Battle of Ilipa, 206 BC

In the spring, Mago joined Hasdrubal Gisco at Ilipa. Together they constituted a force estimated at 54,000 men. Scipio, depending upon whether you believe Polybius or Livy, may have had an equivalent number of men, 55,000. After a cavalry battle in which the Carthaginians were driven back to their camp with heavy losses, both armies engaged in posturing by marching out of camp and facing each other fully deployed. The initiative here seemed to be with the Carthaginians, because they would always deploy first. Only then, would Scipio march out with his troops.

Scipio Africanus at Ilipa, Initial Deployment

In his deployment, the Roman and Italian troops always occupied the center with Iberian allies on the wings along with the cavalry. The Carthaginians would deploy with their Libyan spearmen in the center and Iberians on the wings. This went on for a number of days until Scipio decided to grasp the initiative. One morning he woke his soldiers early and had them eat their breakfast before daybreak. Then he sent his cavalry and velites to harass the Carthaginian outposts. Next he marched out his entire army but placed it much nearer the Carthaginian camp than usual. Also, this time, instead of the Roman legions and their Italian allies being in the center, they were deployed on the wings. Scipio’s Iberians were in the center. The Carthaginians, surprised, quickly mobilized and deployed without eating their breakfast. They deployed in the usual manner with their Libyan veterans in the center. By the time they realized that the Roman strength was on the wings and not in the center, it was too late. The Carthaginians could not deploy without great risk. Thus the veteran Libyan troops were fixed in place, faced by Scipio’s Iberians. Scipio then did nothing with the heavy infantry. His light troops and cavalry skirmished and harassed the Carthaginians but his infantry made no move as the hungry Carthaginians waited for the main assault in the heat of the Spanish sun.

After assessing that the empty stomachs of the Carthaginians and the heat of the Iberian sun had had their affect, Scipio commanded his army into motion. As Scipio’s troops advanced, his screen of velites engaged the Carthaginian skirmishing troops, then redeployed to the wings of the line between the Iberian infantry and cavalry. As the Roman line moved toward the Carthaginians, the wings moved faster than the Iberian infantry in the center, eventually forming a concave line, the Roman wings ahead of the center. As they advanced, the wings then executed a complex tactical maneuver, moving from the acies triplex formation to a rapidly moving column that along with its velites and cavalry overlapped the Carthaginian line.

They then struck the Carthaginian wings where the Iberians were stationed while the Roman Iberian allies approached the Libyan spearmen in the Carthaginian center slowly, in effect continuing to fix them, but not engaging.

Initially, the Iberians held their own against Scipio’s Roman and Italian infantry as the Libyan spearmen could only stand and wait. The Roman cavalry drove off the Carthaginian horse while the velites engaged the elephants. As the Roman cavalry returned, after driving off the Carthaginian horse, they helped stampede the elephants into the Carthaginian center. Eventually, the Carthaginian wings broke and the Libyan spearmen were left on their own. Initially, they withdrew in good order but then broke formation for the safety of their camp. Polybius and Livy say that a heavy rain intervened and saved the Carthaginians from a fate similar to that of the Romans at Cannae. Although Gisgo’s army remained intact, protected by their fortified camp, they were demoralized and his Iberian allies deserted in ever increasing numbers over the next few days. He was obliged to retreat but was run down by Roman pursuit.

Ilipa pretty much sealed the fate of the Carthaginians in Spain. It was a grievous loss and the beginning of the end for Carthage on the Iberian Peninsula. Scipio spent the rest of his time in Spain mopping up and punishing the Iberian tribes that had betrayed his father and uncle. After dealing with a mutiny of Roman troops (their payment was in arears), he returned to Rome to stand for political office and the governorship of Sicily. His objective was the invasion of the Carthaginian homeland, Africa.

Scipio in Sicily

Scipio was elected consul at the age of 31, 11 years before the minimum age. He received a posting to Sicily. His opponents in the Senate allowed him to prepare for the invasion of Africa if it wasn’t deleterious to the interests of the state. He wasn’t, however, given any additional resources. He did have access to the banished legionnaire survivors of the battle of Cannae. He also had some garrison troops from the army of Marcellus. Furthermore, through an innovative stratagem, Scipio got the leading families on the island to fund a cavalry arm, horses and all.

Scipio’s enemies in the Senate, made allegations of corruption, misuse of funds and incompetence. The Senate sent a commission to investigate. What they found was a well-trained and highly motivated invasion force.

PHASE V

Endgame

Scipio in Africa

204-202 BC

Scipio landed in Africa in 204 BC with more than 30,000 battle-hardened troops; 8 oversized legions of 6,500 men each. He and his army landed at the city of Utica, north of Carthage.

The first engagement was a force of 500 Carthaginian cavalry roughly handled by the Roman cavalry. Next, Hanno with 4,000 cavalry was lured by Massinissa and his 2,000 Numidians into an incautious pursuit. Hiding behind some hills was Scipio’s cavalry which struck the Carthaginians in the flank. It was a disaster for the Carthaginians and their leader. Hanno, as well as many of the youth from Carthage’s leading families, perished in the ambush.

Scipio, after this win, returned to his siege of Utica. Syphax and Hasdrubal appeared before his army with 80,000 troops. Most of these were raw recruits but their presence forced Scipio to raise the siege and go into winter quarters.

The following year, Scipio took advantage of an opportunity to attack two camps, the Numidian, led by Syphax, and Carthaginian, in the middle of the night. His soldiers set fire to both camps and waited at the gates as the sleeping soldiers awoke in panic and tried to escape the conflagration. The result was a slaughter in which 40,000 men perished. This destruction of an opposing force was not even a battle. Syphax, the Numidian king was pursued, captured and dethroned. Massinissa, now allied with Scipio, replaced him. This event, more than any other, was a strategic shift in the correlation of forces. It deprived the Carthaginians of what had been a superior arm of their military, the Numidian cavalry, and gave it to the Romans. It was this arm of the military that would be the difference between victory and defeat at the battle of Zama.

After the slaughter of the Numidian-Carthaginian camps, Carthage was vulnerable to Scipio’s army. Thus they began negotiations. Scipio’s terms were lenient. However, Hannibal and his army had been recalled to Africa. As he landed his troops, the Carthaginians broke off negotiations, casting their lot with their undefeated general.

Scipio, instead of meeting Hannibal near Carthage, headed southwest along with Bagradas Valley toward the interior. This move threatened the Carthaginian economic base and it placed the Roman army within close proximity to Numidia and Massinissa his new ally. This caused concern in Carthage and Hannibal was obliged to follow. Below is a description of a related event by BH Liddell Hart.

He [Hannibal] then sent out scouts to discover the Roman camp and its dispositions for defence—it lay some miles farther west. Three of the scouts, or spies, were captured, and when they were brought before Scipio he adopted a highly novel method of treatment. “Scipio was so far from punishing them, as is the usual practice, that on the contrary he ordered a tribune to attend them and point out clearly to them the exact arrangement of the camp. After this had been done he asked them if the officer had explained everything to their satisfaction. When they answered that he had done so, Scipio furnished them with provisions and an escort, and told them to report carefully to Hannibal what had happened to them” (Polybius). This superb insolence of Scipio’s was a shrewd blow at the moral objective, calculated to impress on Hannibal and his troops the utter confidence of the Romans, and correspondingly give rise to doubts among themselves. This effect must have been still further increased by the arrival next day of Massinissa with six thousand foot and four thousand horse. Livy makes their arrival coincide with the visit of the Carthaginian spies, and remarks that Hannibal received this information, like the rest, with no feelings of joy.

Hart, B.H. Liddell. Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon (pp. 154-155). Da Capo Press. Kindle Edition.

Hannibal, impressed by Scipio’s magnanimity and confidence, asked for a face-to-face meeting with Scipio. Scipio obliged but first he relocated his camp on a hill close to water. Hannibal also moved his camp near the proposed meeting site but his camp was not so near water. This caused his men hardship.

Reportedly, the meeting was cordial. Hannibal asked Scipio who he considered the best general ever. Scipio answered Alexander the Great.

Hannibal tried to avoid an all-out battle, hinting that fortune could be fickle, but Scipio was confident in his chances of success.

Hannibal first saluted Scipio and opened the conversation. The accounts of his speech, as of Scipio’s, must be regarded as only giving its general sense, and for this reason as also the slight divergences between the different authorities may best be paraphrased, except for some of the more striking phrases. Hannibal’s main point was the uncertainty of fortune—which, after so often having victory almost within his reach, now found him coming voluntarily to sue for peace. How strange, too, the coincidence that it should have been Scipio’s father whom he met in his first battle, and now he came to solicit peace from the son! “Would that neither the Romans had ever coveted possessions outside Italy, nor the Carthaginians outside Africa, for both had suffered grievously.” However, the past could not be mended, the future remained. Rome had seen the arms of an enemy at her very gates; now the turn of Carthage had come. Could they not come to terms, rather than fight it out to the bitter end “I myself am ready to do so, as I have learnt by actual experience how fickle Fortune is, and how by a slight turn of the scale either way she brings about changes of the greatest moment, as if she were sporting with little children. But I fear that you, Publius, both because you are very young, and because success has constantly attended you both in Spain and in Africa, and you have never up to now at least fallen into the counter-current of Fortune, will not be convinced by my words, however worthy of credit they may be.” Let Scipio take warning by Hannibal’s own example. “What I was at Trasimene and at Cannæ that you are this day.” “And now here am I in Africa on the point of negotiating with you, a Roman, for the safety of myself and my country.

Hart, B.h. Liddell. Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon (pp. 156-158). Da Capo Press. Kindle Edition.

The battle of Zama was a close call. It took the return of the Roman and Numidian cavalry to the field of battle and its strike against Hannibal’s veteran reserve to seal the victory. But it wasn’t just luck. If the goddess Fortuna smiled upon Scipio, it was not on a whim. She favored him because his extensive and thorough preparation made it impossible for her not to. Scipio did everything he could to give his troops an advantage against a formidable opponent that the Romans had never defeated on the field of battle.

- Scipio used diplomacy to court the Numidian Kings Syphax and Massinissa; efforts that would pay dividends when it came to making the cavalry arm a Roman strength instead of a weakness

- Scipio transformed his velites (light infantry), from a liability, into a competent component of the legion; they would play a key role in the opening phase of the battle of Zama against Hannibal’s elephants

- In Sicily, on his own, and despite obstruction from the Senate, Scipio created a heavy cavalry arm which together with the Numidians would drive the Carthaginian cavalry from the field and decide the battle

- He integrated the exiled survivors of Cannae with elements of Marcellus’ veterans into well-honed heavy infantry, the core of his army for the African campaign

- He accumulated supplies to feed his army and a fleet to transport it to Africa

- In Africa, he destroyed two large armies (80,000 men), Numidian and Carthaginian, at almost no cost to himself, forcing Hannibal’s recall from Italy

- Once in Africa, he made a strong strategic move by marching west along the Bagradas valley thereby threatening the Carthaginian hinterland and her economy, placing his army near the Numidian border in close proximity to Massinissa and his formidable Numidian cavalry

Scipio’s battlefield tactics at Zama

- During the opening phase, Scipio had his trumpeters blast their trumpets, thereby frightening Hannibal’s elephants during their initial charge

- The alignment of the cohorts also allowed Hannibal’s charging elephants to follow the path of least resistance and pass through the Roman lines with a minimum of disruption

- Scipio aligned his cohorts in vertical columns instead of the usual checkerboard pattern so that his velites could retreat easily when Hannibal’s elephants charged; many of the velites were able to redeploy in the lateral pathways between the ranks of maniples and pepper the elephants with their darts

- In the second phase of the battle, Scipio’s horse drove Hannibal’s cavalry from the field, the reverse of what had happened during Hannibal’s previous battles with the Romans

- In the third phase of the battle, the Roman heavy infantry was able to redeploy from the acies triplex to a single unbroken line

- During the fourth phase of the battle, the Roman heavy infantry defeated the first two lines of Carthaginian mercenaries

- During the fifth phase of the battle, the Roman heavy infantry engaged Hannibal’s veterans, his reserve, and fought them to a draw until the Roman cavalry returned to the field and struck the Carthaginians in the flanks and rear

Hart, B.h. Liddell. Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon (pp. 156-158). Da Capo Press. Kindle Edition.

Titus Livy. History of Rome. Book XXXIV.4 Trans. Rev. Canon Roberts. Editor. Ernest Rhys Titus. Publisher. J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd. London, 1905.

Consequences of the 2nd Punic War

The war with Carthage brought significant changes to the Roman state and accelerated other changes that were taking place already.

- Rome lost a quarter of her citizens in the fighting

- Stressed the economy: severe inflation; devaluation of the coinage

- Forced to double taxes on citizens (tributum)

- Further professionalization of the army; generals now had appointments that lasted more than one calendar year

- Huge transfer of wealth from Capua, Tarentum, Syracuse and other cities to Rome; this increased wealth had a profound effect on Roman citizens, especially the aristocracy and business class

- Stressed the Roman-Italian alliance; allies had little to show for their suffering during the war

- Added provinces to the Roman state; these had to be administered and were seen as prizes for political success