216 BC

Battle of Cannae

Sources

There are four sources upon which this section rests; Polybius, Livy, Dodge and O’Connell.

O’Connell on Polybius

Polybius probably worked on his Rise of the Roman Empire at least 50 years after Cannae took place. O’Connell tells us that he interviewed Gaius Laelius, an adjutant to Scipio Africanus (key commander in Iberia and in Africa). He also met with Massinissa, the Massylian prince who eventually ruled Numidia. He was a key asset to the Carthaginians and later to Scipio Africanus at the battle of Zama. O’Connell also says that Polybius may have met with some survivors of Cannae although that means that they must have been very old. Polybius also consulted previous authors’ histories; Fabius Pictor, a relative of the delayer (Cunctator) Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus. More importantly, he read the work of L. Cincius Alimentus, a Roman officer who was Hannibal’s prisoner of war and who got to know the Carthaginian general quite well. Polybius also had access to literature on the Carthaginian point of view. Two historians, Sosylus the Spartan and Silenos from Kaleakte, traveled with Hannibal to Italy and stayed with him on his campaigns. But most important of all, Polybius was a military man. Consequently, unlike Livy, he understood the role of military training, logistics, battlefield ground and tactics first hand.

O’Connell, Robert L. The Ghosts of Cannae: Hannibal and the Darkest Hour of the Roman Republic. Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Locations 208-9/6372.

O’Connell on Titus Livius (Livy)

Unlike Polybius, who was a hipparchos (commander of cavalry, 500 men), Livy was not a soldier or a politician. Nor did he visit battle sites as did Polybius. Furthermore, he was writing some 87 years after Polybius’ death and 170 to 190 years after events during the Second Punic War, so personal interviews with the participants were not possible.

O’Connell describes Livy as having more in common with a Hollywood cinematographer than a historian, more interested in creating a good dramatic scene that would entice the Roman reader than in historical accuracy. This is to some extent true. Livy was an excellent stylist and dramatist. And though he relied upon some of the same respected history sources as did Polybius, Silenos of Kaleakte and Fabius Pictor, his focus was more on literary allusion and a deep understanding of the events he was describing and how those events related to the greatness of Rome.

In contrast to O’Connell, scholars generally take Livius much more seriously as a historian. He was, they claim, just using a different set of literary conventions. Even though he used the annalistic structure, dividing his narrative by year and naming the consuls during whose tenure events took place, his history was also strongly thematic and intertextual.*

*By intertextual is meant that Livius would allude to or reference literary works with which his audience was familiar in order to deepen the meaning of a particular segment of his work on the Hannibalic War.

Levene DS, Livy on the Hannibalic War Oxford University Press. Great Clarendon Street, Oxford. 2010 p.viii.

O’Connell RL, The Ghosts of Cannae. Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. New York. ©2010. Kindle Edition. Location 110-227/6372.

For example, D.S. Levene, in the preface to his Livy on the Hannibalic War claims that “Livy’s Third Decade, his narrative of the Hannibalic War, is the most remarkable and brilliant piece of ‘sustained’, ‘prose’, and ‘narrative’…”

Levene DS, Livy on the Hannibalic War Oxford University Press. Great Clarendon Street, Oxford. 2010 p.vii.

Dodge

Theodore Ayrault Dodge received his military education in Berlin and his university education in London and Heidelberg. When the Civil War broke out in the States, he volunteered for duty as a private in the Union army with the New York Volunteers. He lost his right leg at the battle of Gettysburg. Afterward, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the war department. By the end of the war he was brevetted a Lieutenant Colonel. His military education in Germany and his experience as a regular foot soldier and as an officer during the Civil War and later as a military bureaucrat made him singularly qualified to write about military matters. Furthermore, he visited the various battlefields of the Second Punic (Hannibalic) War.

What makes Dodge such a dependable narrator is that his experience, despite technological advancements over what the ancients used, was very much like that of those ancient warriors. The Union army still used horses and pack animals, fought in close formation, used trumpets and bugles to announce coordinated maneuvers on the battle field, engaged in distant as well as in close-quarter combat. Furthermore, battlefield ground was extremely important and Dodge knew well how to assess it.

O’Connell

Robert L. O’Connell was educated at Colgate University and the University of Virginia, where he received a Ph.D. in history. He worked for three decades in the U.S. Intelligence Community, before becoming a Visiting Professor at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey California. Unlike Dodge, O’Connell did not serve in the military nor did he visit any of the Punic War battle sites. However, O’Connell has a huge body of scholarly work to stand on regarding ancient texts dealing with the Punic Wars. And he’s focused much of his writing on military history.

O’Connell in his Ghosts of Cannae, discusses his major sources for the battle of Cannae. He trusts Polybius the most and seems to undervalue Livy. What is especially useful about O’Connell’s book is his focus upon the Roman military system and how it functioned, upon the Roman military mind, upon the experience of the Roman and Italian troops, and upon Roman and Italian losses in the previous two years to Cannae and how that affected the quality of the troops at Cannae.

For example, he writes that the Roman defeats at Ticinus, Trebia and Lake Trasumennus must have been particularly hard on the cavalry. At Ticinus, it was the Roman and Italian cavalry and light infantry that faced Hannibal’s cavalry; the heavy Carthaginian, Iberian and Gallic horse as well as the highly effective Numidians. The Hannibalic cavalry managed to keep the field after the fight. At Trebia, the Roman and Italian cavalry was driven off the battlefield by the heavy cavalry and the Numidian light horse, leaving the flanks of the Roman wings unprotected. At Trasumennus, the entire Roman army was ambushed and the cavalry along with the infantry was massacred. The Roman and Italian cavalry was never the primary arm of the Roman military system. It was the heavy infantry—reorganized after its defeat at the Alia River by the Gauls in 390 BC—that was at the core of Roman battlefield effectiveness.

O’Connell tells us that the Romans had 20,000 light infantry (velites) at Cannae. And he is skeptical about their effectiveness. Keep in mind that the velites were the poorest and youngest troops in the legion; too poor to pay for a helmet (galea), body armor (a pectoral plate or chain mail/lorica hamata), a full protective shield (scutum) and a cutting-thrusting sword (gladius). O’Connell writes that Hieron of Syracuse offered the Romans 1,000 of his light infantry before the battle. His archers were the only archers that the Romans had at Cannae. Overall, O’Connell doesn’t think the Roman light infantry measured up to Hannibal’s skirmishers, although it seems they held their own in the opening phase of the battle at Cannae.

The Roman and Italian heavy infantry when fighting in formation in a disciplined manner were virtually unbeatable. They proved it at Trebia when 10,000 of them cut through the Gallic center and marched to safety while their fellows on the wings were being slaughtered. This also happened at Trasumennus, although they were later forced to surrender.

The Battle

The First Day

The battle of Cannae took place over the course of three days in the summer of 216 BC. On the first day, according to Polybius and Livy, both armies were in their respective camps south of the Aufidus River. The Carthaginian camp was near Cannae, a locality with large storage facilities for Hannibal’s army. The Roman camp was not far from Canusium. The two camps were separated from each other by five miles of flat, treeless ground.

That morning, as the Roman army marched under Varro’s command, Hannibal mobilized his light infantry and all of his cavalry and attacked the Roman column. He threw the Roman formation into confusion. However, the Romans took the initial Carthaginian thrust and maintained their integrity by bringing up the heavy infantry. These were reinforced later by the velites and cavalry. Thus the Romans began to get the better of the fighting. The onset of darkness ended the fighting. The Romans had won the first day. Hannibal never committed his heavy infantry to battle.

Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire. Ian Scott-Kilvert (Trans.), 1979. Penguin Books, Ltd. London. Kindle Edition. Location 4254-4272/9638.

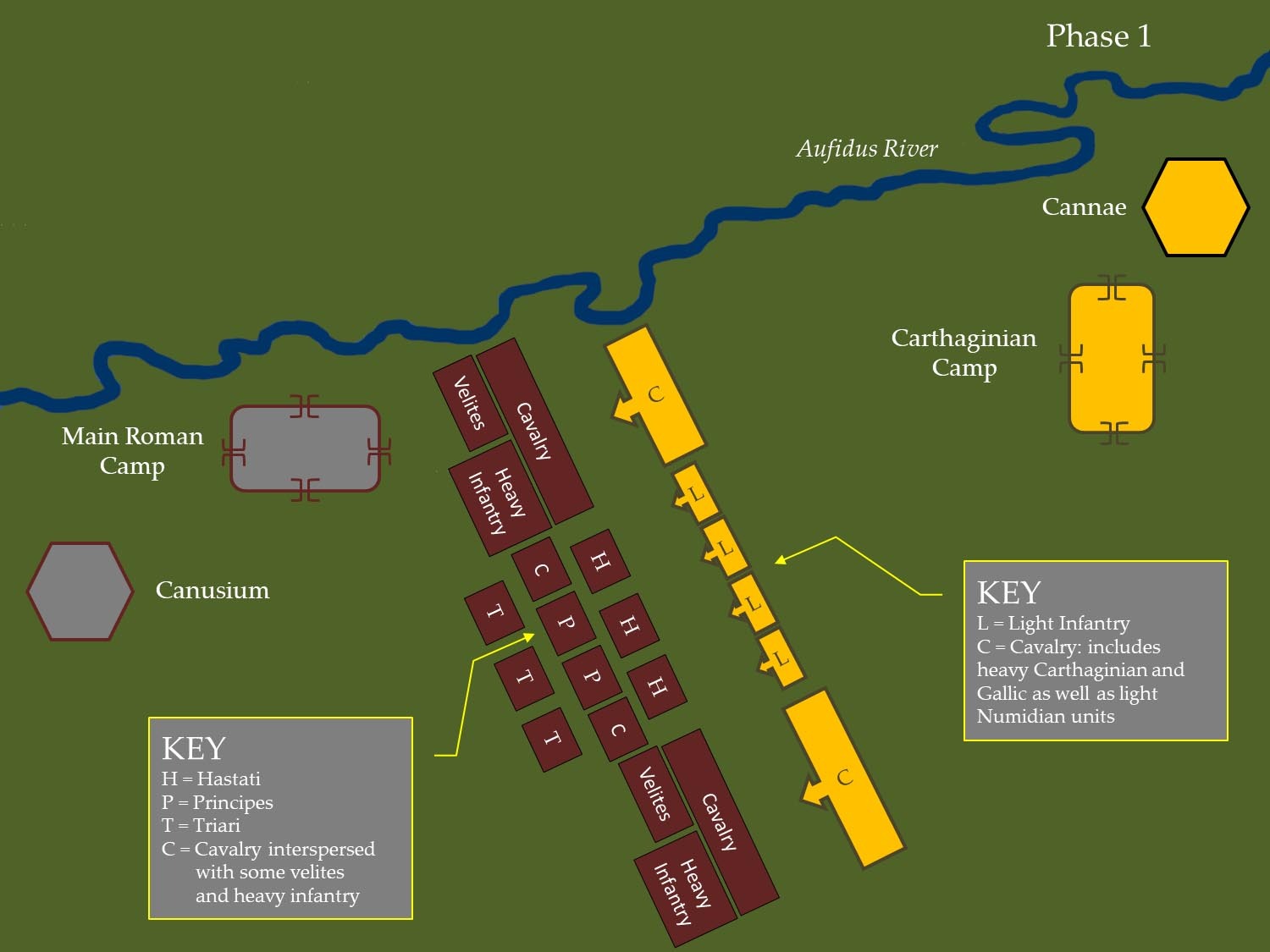

Cannae–Phase 1

On day 1 of the battle of Cannae, Varro commanded the army. Varro offered Hannibal battle and he accepted. Hannibal deployed 8,000 light infantry and all of his cavalry. They charged the Roman lines and though hard pressed the Romans held. This was in part because Varro had supported his infantry with cavalry interspersed with velites and heavy infantry.

The Second Day

The second day, the Consul Paulus took command of the army. Being more cautious than Varro, Paulus built a smaller camp on the north bank of the Aufidus River and populated it with several thousand men in order to provide support for Roman foraging parties. In response Hannibal had his Numidians cross the river and harass the Roman water carriers. Nevertheless, still not satisfied with the ground on which the armies would fight, Paulus would not accept Hannibal’s provocations. Varro would, however, prove to be a more offensive-minded commander.

The Third Day

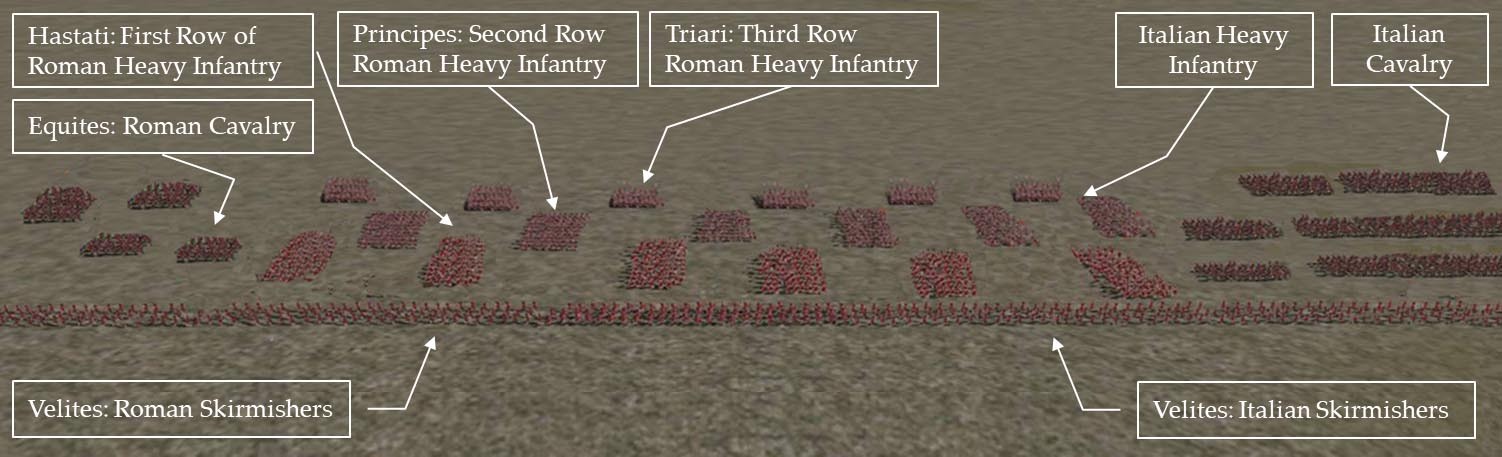

Early in the morning, Varro, now commanding the army, concentrated the Roman army on the north side of the Aufidus River. He anchored his right wing, Roman cavalry, on the small fort close to the north bank of the river. Next he placed his Roman legions, not in their usual configuration but with a narrower front and greater depth. He still employed the acies triplex (three lines of heavy infantry; Hastati, Principes and Triari). The eight Italian alae assembled to the Roman left. On the left wing was the allied cavalry. Fronting the Roman army were the velites (skirmishers).

Roman Army at Cannae

Under Varro, the intervals between maniples were reduced and individual units were arranged vertically, with a narrow front but much greater depth. This was done because Hannibal had anchored the two wings of his army against the River Aufidus and thus had a limited front but protected flanks. The Romans had significantly more infantry and if not for the protection of the river on either Carthaginian side would have overlapped the Carthaginian line.

Carthaginian army at Cannae

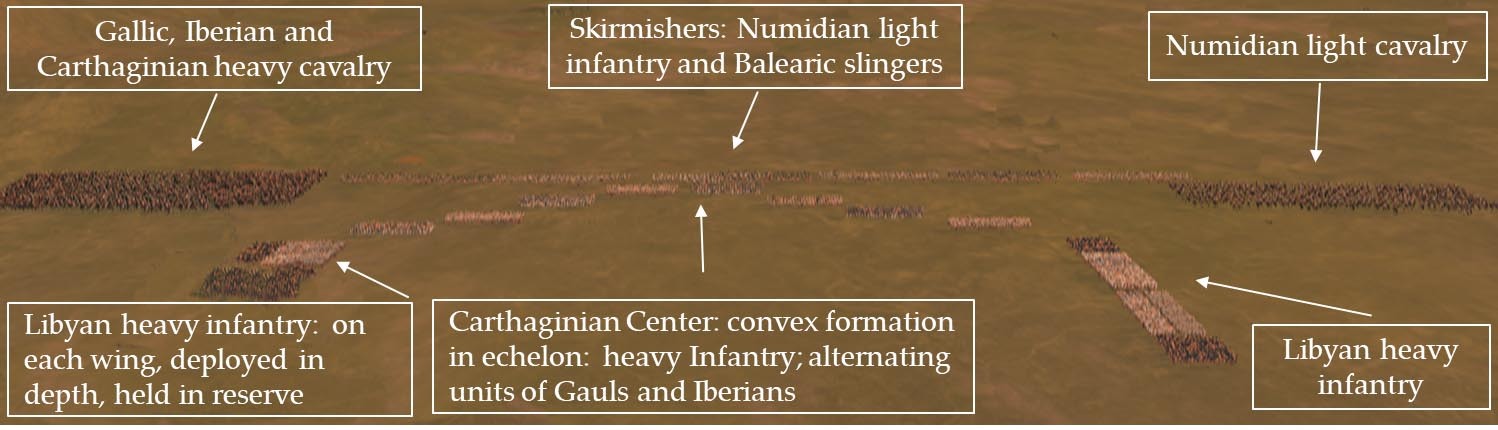

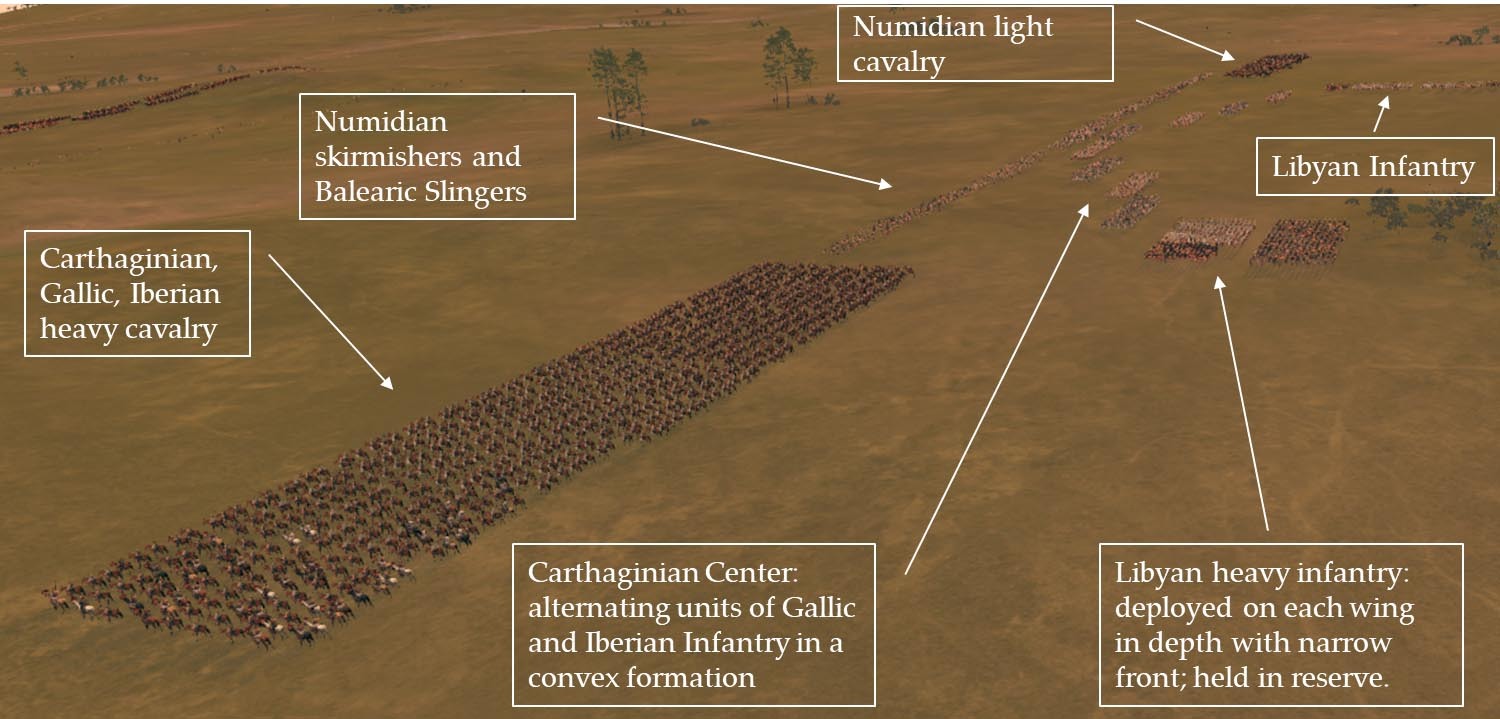

With skirmishers screening the deployment of his heavy infantry and cavalry, Hannibal arranged his center in a convex formation with alternating units of Gallic and Iberian heavy infantry. To the left and right of the center, he placed his Libyan spearmen, deployed in depth. These units were held in reserve. To the left of the Libyans were the Gallic, Iberian and Carthaginian heavy cavalry. On the right was the Numidian light cavalry.

Carthaginians at Cannae-deployment

Carthaginian Dispositions at Cannae, Side View.

Hannibal, accepting Varro’s challenge, launched his skirmishers and slingers along the entire Roman front. They masked his deployment which followed the fording of the Aufidus River in two columns. Hannibal placed his Carthaginian and Gallic heavy cavalry on his left flank facing the Roman horse. Next he placed his veteran African infantry. In the center he placed the Gauls and Iberians, alternating ethnic companies in a convex formation. To their right was another division of African heavy infantry. On the right wing were 2,000 Numidian light cavalry, facing Italian horse. The Romans, in all likelihood, had 86,000 men. The Carthaginians deployed significantly fewer men, perhaps 50,000. The convex center of the Carthaginian line, which stood in advance of the wings, was to engage the Roman infantry first. The African veterans on each wing would function as a reserve.

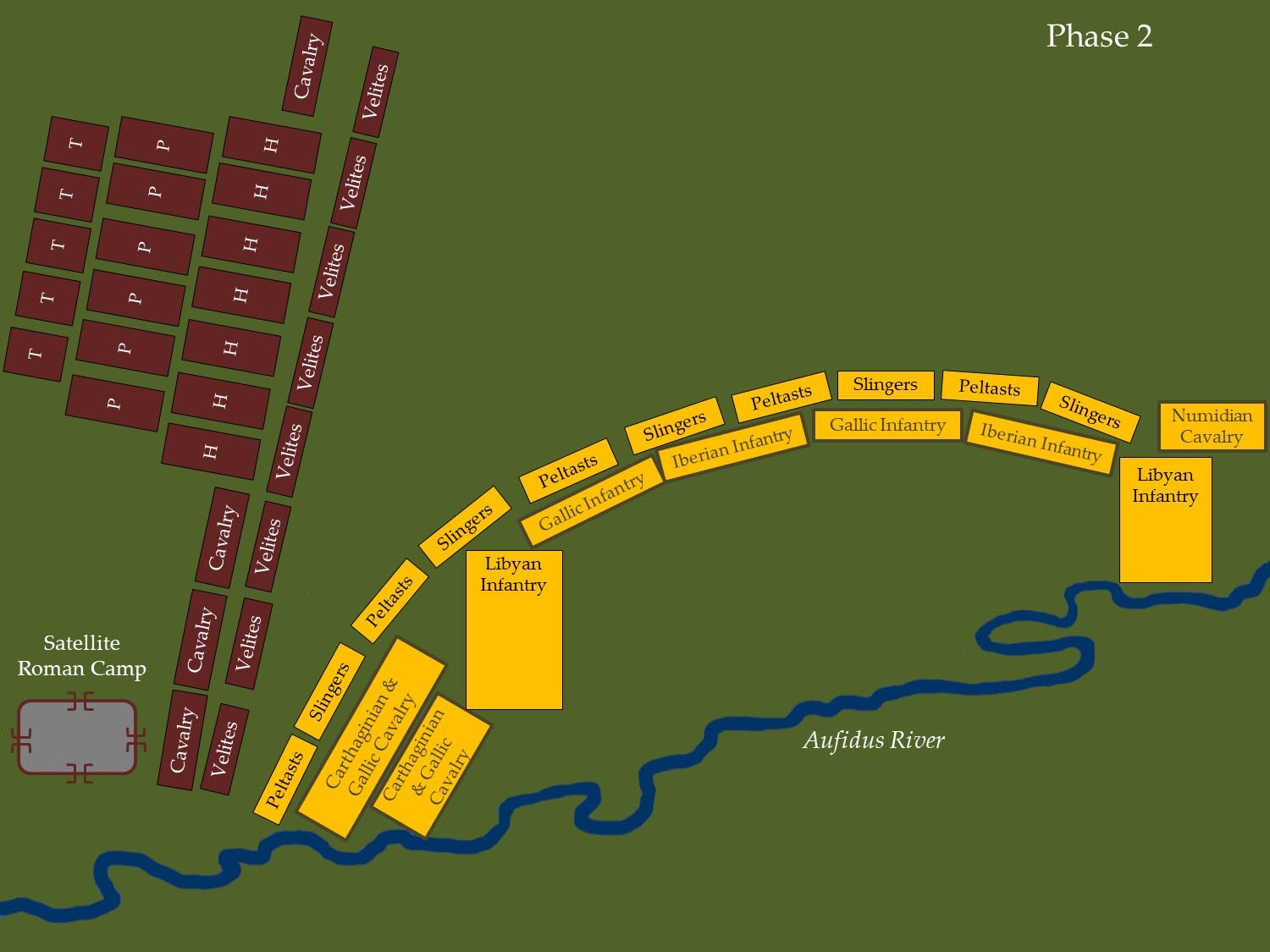

Cannae—Day 3, Phase 2

Varro deploys his entire army, anchoring his right wing on the small Roman fort. His heavy infantry is aligned in depth along a front that matches the Carthaginian front. The skirmishers precede them.

Hannibal anchors both his wings on the Aufidus River.

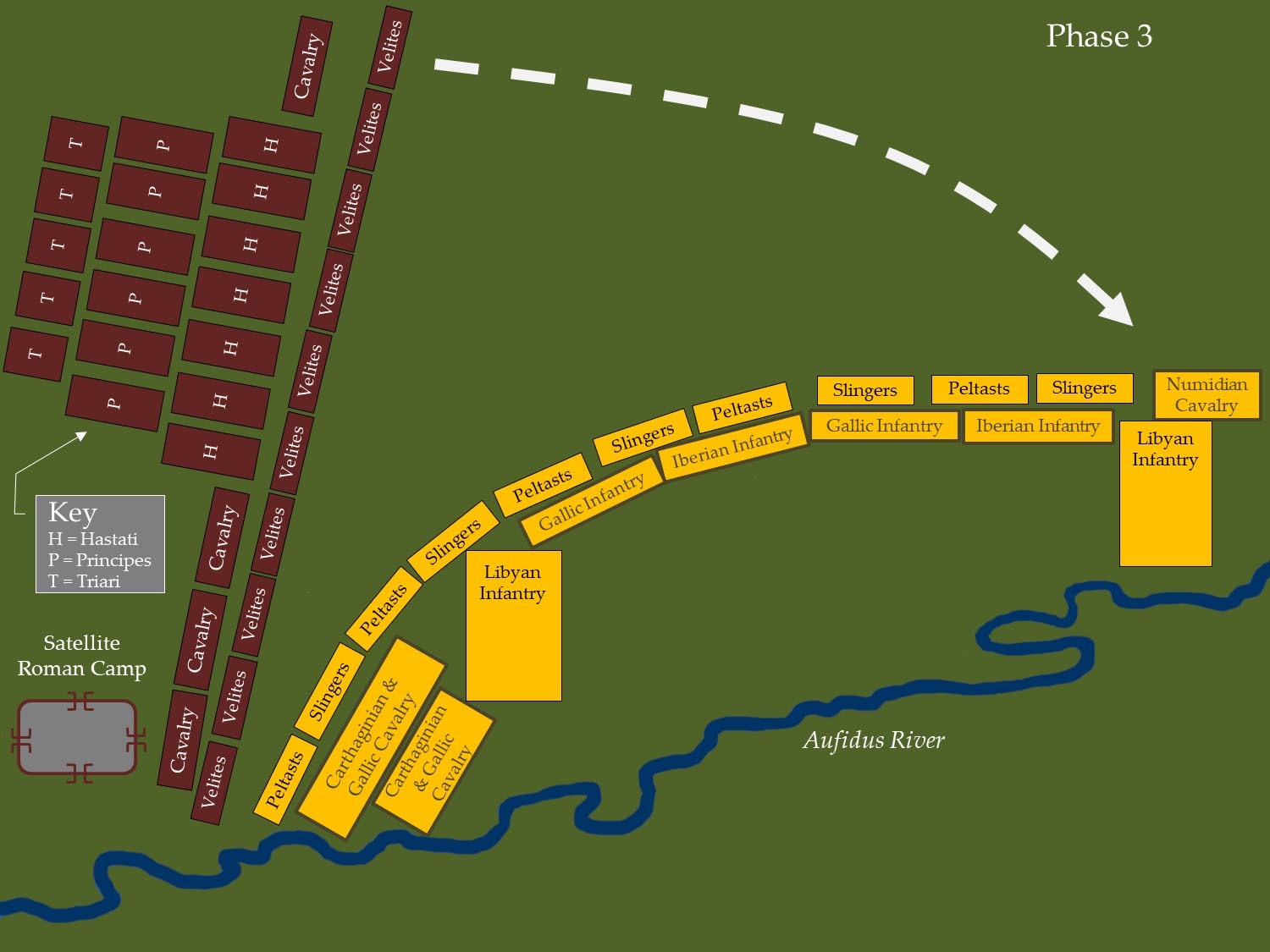

Cannae—Day 3—Phase 3

Hannibal anchored both of his wings on the Aufidus River in order to prevent being overlapped by the greater Roman numbers. Varro has his army wheel south in order to match up with the Carthaginian line.

As the fighting began, the struggle between the light infantry of each army was even. Then the heavy cavalry on the Carthaginian left wing charged the Roman cavalry. The fighting was intense. Even though the Romans kept their ground, eventually, superior Carthaginian training and numbers began to tell. The Roman cavalry either perished or was driven from the field. Paulus was wounded in this phase of the fighting.

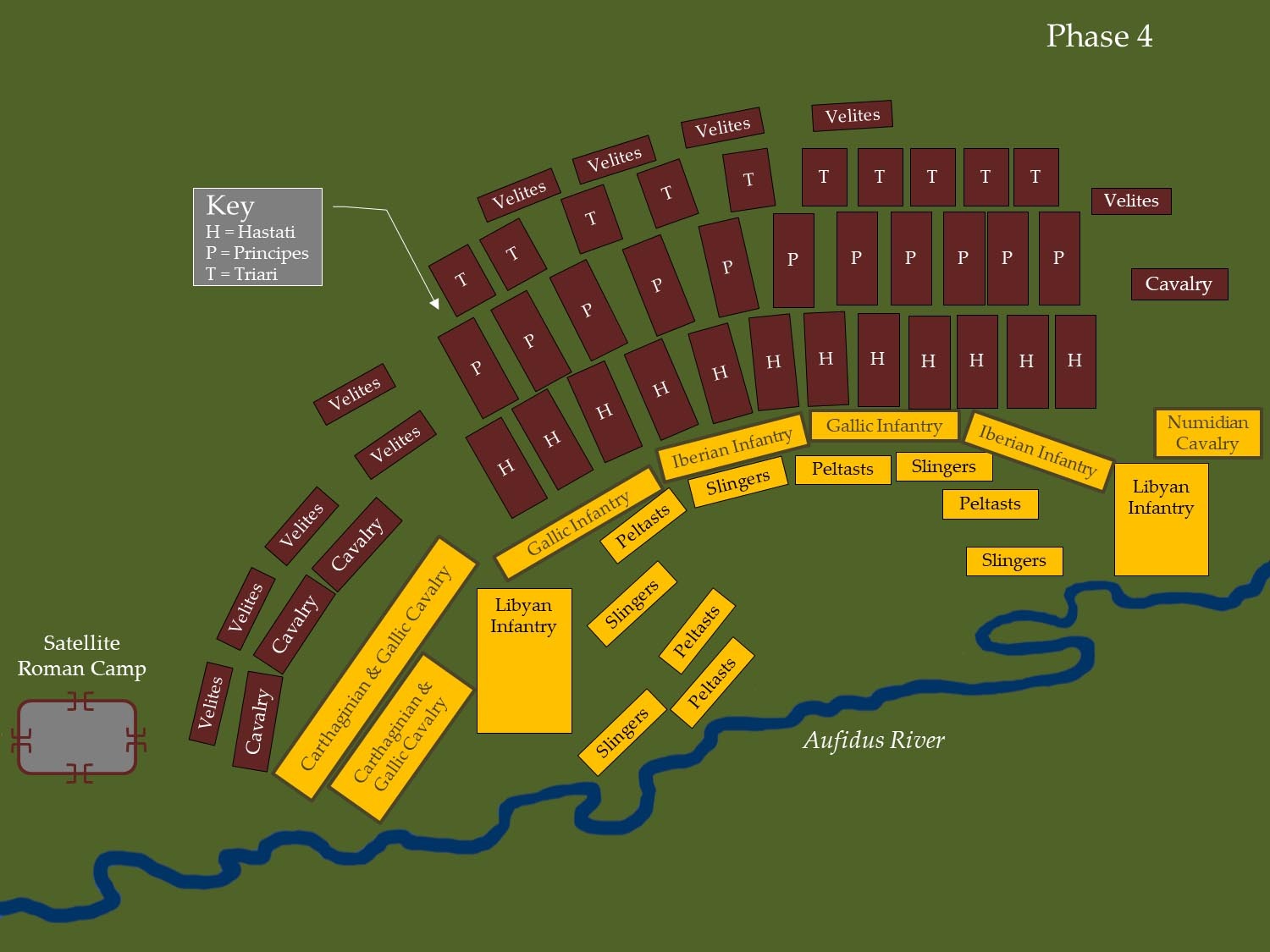

Cannae—Day 3—Phase 4

Both skirmishing lines, after intense fighting, retreated behind their heavy infantry; the Roman velites behind and interspersed between the Triari and the Carthaginian light infantry and slingers behind their cavalry and heavy infantry.

In the meantime, both skirmishing lines had retreated behind their heavy infantry; the Velites in and amongst the Triari and the Carthaginian peltasts and Balearic slingers behind their heavy infantry.

Cannae—Day 3—Phase 5

The heavy Carthaginian, Iberian and Gallic cavalry on the left flank attacks the Roman cavalry on the Roman right. The fighting is intense, with the Carthaginians eventually driving the Roman cavalry off the field. Meanwhile, on the right wing, the Numidians keep the Italian cavalry occupied.

While the heavy cavalry was engaged on the left wing, the Numidians skirmished with the Italian cavalry on the right. But this was merely a holding action, to keep the Italian cavalry occupied.

In the meantime, the Gauls and Iberians in the center made contact with the center of the Roman and Italian heavy infantry. The Roman center slowly pushed the Gauls and Iberians back.

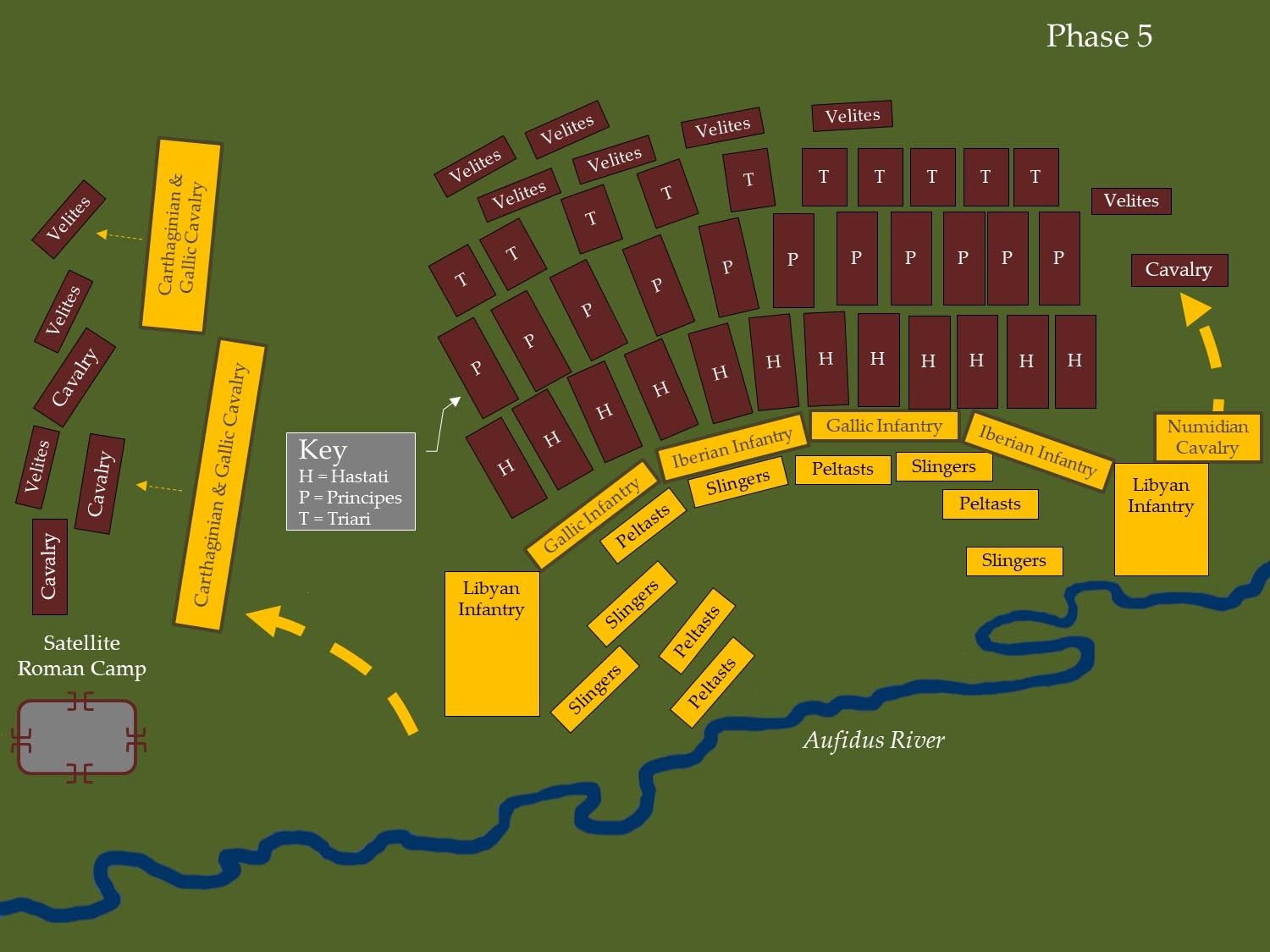

The heavy cavalry drove the Roman cavalry off the field or slaughtered them where they stood dismounted. They then regrouped and skirted the rear of the Roman infantry and struck the Italian cavalry on the opposite wing from the rear.

The cavalry on the left wing of the Roman army disintegrates. The Numidians pursue the remnants while the heavy Carthaginian, Gallic and Iberian cavalry regroups and rests.

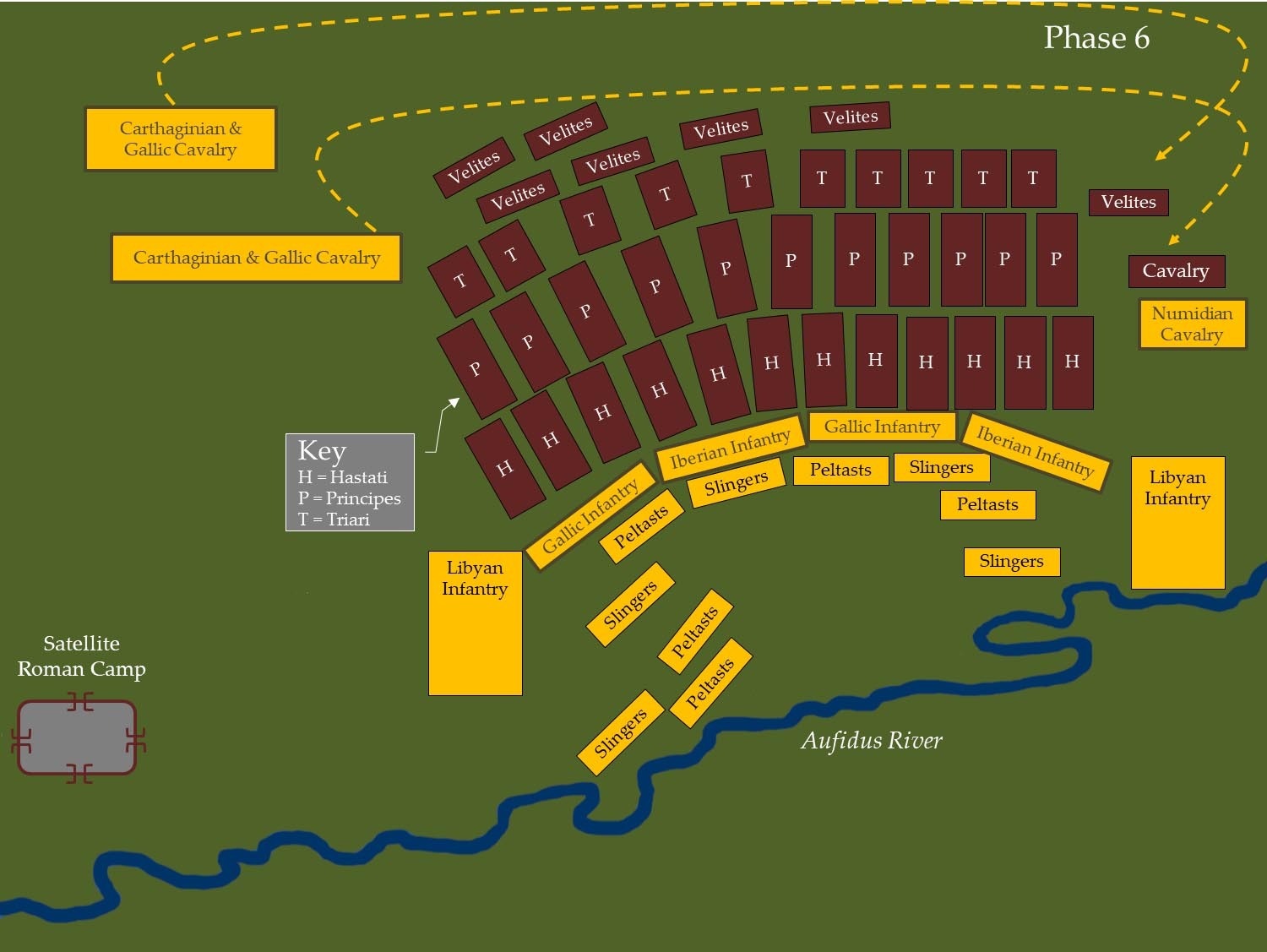

Cannae—Day 3—Phase 6

After the Carthaginian heavy cavalry drives the Roman cavalry from the field, it skirts the rear of the Roman infantry and hits the Italian cavalry on the Roman left wing from the rear.

The Roman infantry, meanwhile, is successfully pushing back the Carthaginian center and like water, which flows to fill an empty space, occupies the ground liberated from the enemy.

Cannae—Day 3—Phase 7

The Roman army has no cavalry and no infantry reserve. The Carthaginian heavy cavalry has now rested and regrouped to the rear of the Roman infantry.

After regrouping, the Carthaginian heavy cavalry, now rested, begins to charge sections of the Roman infantry from the rear. Normally they would face the Triari, who would reverse field and create a defensive shield wall bristling with spears. Horses won’t charge a shield wall. But what they probably faced was a mixture of vulnerable Velites and Triari. Because of what was happening up front in the center, a strong Roman push—the heavy infantry formations were flowing into the gap created by a slowly retreating enemy—the Roman maniples were losing their cohesion. At the same time, the Velites would be seeking refuge from the charging heavy cavalry behind their own heavy infantry. But there was no room for them. That is when panic ensued and vulnerable Velites would probably have disrupted the Triari formation.

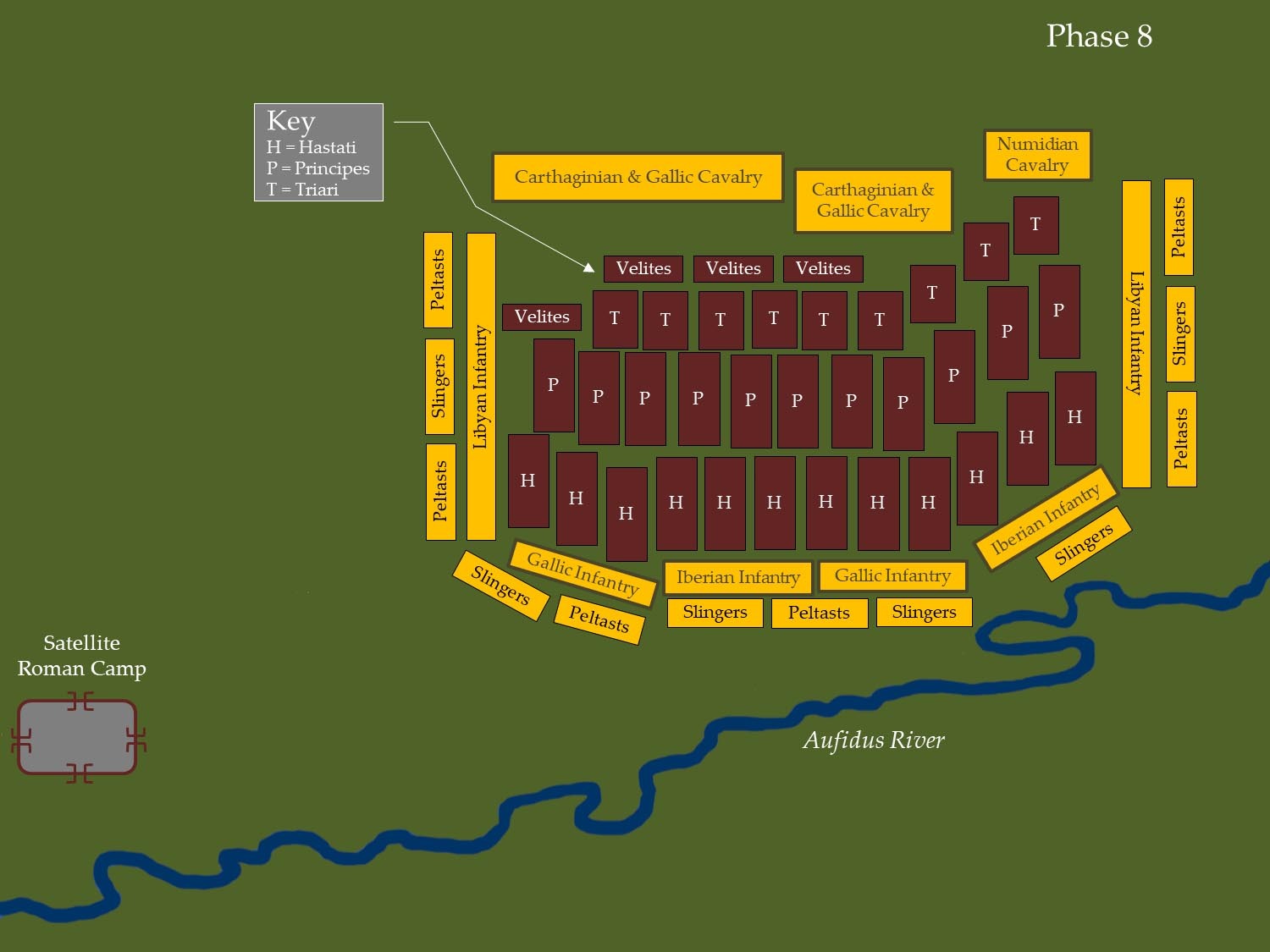

Cannae—Day 3—Phase 8

Along the Roman flanks, the Libyans, who were originally deployed on the wings in an in-depth echelon formation, moved forward and secured the left and right side of the Roman formation.

As the Carthaginian heavy cavalry was destroying the Italian Cavalry on the left wing after it had crushed the Roman cavalry on the Roman right wing, and the Roman infantry had pushed the Carthaginian center back, the Libyan infantry deployed along both, now unprotected, Roman flanks. The heavy Carthaginian, Gallic and Iberian horse had regrouped and begun charging the Roman rear.

The Roman army was surrounded, on both flanks by Hannibal’s formidable heavy Libyan infantry veterans, in the front by the Gallic and Iberian heavy infantry that had stopped retreating and in the rear by the Carthaginian heavy cavalry and light Numidian horse. Behind the heavy infantry were the Numidian javelin skirmishers and Balearic slingers.

Within the surrounded Roman force, the maniples which had already been placed at closer intervals than usual, it had become more difficult to maneuver as the Carthaginian army pressed the Romans at the periphery, forcing them back toward the center.

The Romans would not know what was going on. With the dust raised up by so much cavalry and infantry, vision would have been limited. Furthermore, there was a southeasterly wind that blew in that part of the country during that time of the year. So the dust would have been carried by the wind toward the Roman lines.

Cannae, POV of Triari; Carthaginians raising dust

In the Distance, Dust Raised by Deploying Carthaginians Obscures Roman Vision-Point of view: Triari.

It is unclear at this stage of the campaign, how the Libyan spearmen fought, phalanx or Roman style. In Spain and at Trebia and Trasumennus, they had fought in the typical Hellenistic phalanx formation. But we read in Polybius that Hannibal “as soon as he had won his first battle discarded the equipment with which he had started out, armed his troops with Roman weapons, and continued to use these till the end of the war.” Irrespective of their fighting style, they were able to contain the Roman infantry and that was the beginning of the end for the Roman army at Cannae.

Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire (Classics) (Kindle Locations 8037-8038). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

The average Roman soldier, according to Polybius (18.28–30), needed a six-by-six foot box in which to function effectively. The Carthaginians were able to reduce that to a three x three foot space and as they pressed in from the edges, the room for maneuver became more and more constricted until no motion was possible at all.

O’Connell, Robert L. The Ghosts of Cannae: Hannibal and the Darkest Hour of the Roman Republic (Kindle Locations 920-922). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

The soldiers at the periphery were facing an impenetrable shield wall on the flanks, the previously exultant infantry at the front of the formation faced a now revivified heavy infantry of Gauls and Iberians, and those in the rear were being repeatedly run down, trampled and pierced by the formidable heavy cavalry. These were veteran Hannibalic troops who knew how to kill efficiently. They had already killed at least 70,000 Romans and Italians in the three victories they’d gathered previously. The deadly Balearic slingers would be pelting the troops deeper in the trapped mass with their lethal lead and stone bullets. The Numidian peltasts would release their javelins in waves and they couldn’t miss because of the density of the enemy troops. The screams of the dying and wounded, the moans and cries of terror of those who had lost their footing in the churned up mud slick with blood, vomit and bodily fluids, the claustrophobic panic of those gasping for air as they were being pressed against each other ever harder, only added to the general din and the feeling of hopelessness. The August Sun must have been enervating; men collapsing where they stood from heat exhaustion and thirst.

The killing of an army as large as that at Cannae would have taken a long time. Keep in mind that this was heavy infantry, which carried between 50 and 80 pounds of armor and arms per man. And they were fighting in the August heat under the southern Italian sun. Under such conditions, the frontline troops would be able to fight for perhaps 15-20 minutes at a time. Then they would need to recuperate. So, fighting was not continuous along the front and periphery. Rather it was sporadic. And it wasn’t uniform. The fighting basically devolved into many small battles between maniples, groups of individuals and even individuals. If there were 86,000 infantry at Cannae—with 10,000 left behind in the large Roman camp and 2,000 in the small camp—that leaves 74,000 men. If the battle lasted 12 hours, the Carthaginians would have had to kill more than 6,000 men per hour to achieve near complete annihilation.

Of the 6,000 Roman and allied horse, only 370 escaped. Ten thousand infantry were taken prisoner but these were from the Roman camps and had not taken part in the fight. Of those engaged in battle, only approximately 3,000 escaped, Publius Cornelius Scipio among them.

“On the side of Hannibal there fell four thousand Celts, fifteen hundred Iberians and Libyans, and about two hundred horse.”

Polybius. Complete Works of Polybius (Delphi Classics) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 31) (Kindle Locations 5107-5108). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition.

After The Battle

Consul Varro and, perhaps, 12,000 men survived the battle of Cannae. The rest were either killed or taken prisoner. Hannibal freed Italian allied soldiers without ransom. The Roman prisoners of war were, for the most part, sold into slavery because the Roman Senate wouldn’t ransom them.

Although Varro was welcomed back to Rome and thanked by the senate for his service, the other survivors of Cannae were banished to serve in exile in Sicily. They would remain there for ten years, helping Marcellus besiege Syracusa until the young Publius Cornelius Scipio recruited them for his invasion force of the Carthaginian homeland.

Shortly after Cannae, another consular army, under the Consul Lucius Postumius Albinus, was annihilated in an ambush by the Gauls (Boii) in northern Italy at the battle of Silva Litana. The city of Rome, hearing of the disaster coming on the heels of Cannae, went into mourning. Albinus was replaced as consul by Marcus Claudius Marcellus, the holder of the spolia opima (meaning the best spoils, the highest Roman military honor) for killing the Gallic King Viridomarus in hand-to-hand combat in 222 BC at the Battle of Clastidium.

Fabian military policy was reinstituted, but with a difference. Competent generals received extended commands. The Romans did not seek a win-all battle with Hannibal. Furthermore, with the defection of the city of Capua to the Carthaginian side, the locus of the conflict shifted to Campania. There, the Romans did better than in Gaul, Umbria, and Apulia. They limited Carthaginian expansion in that part of Italy and eventually retook the city of Capua. From this point on, Roman troops found success in Sicily, Sardinia and Spain and Hannibal found himself more on the defensive in southern Italy. Ironically, the cities and tribes that defected to the Carthaginian side had to be protected and proved a drain on limited Carthaginian manpower. Thus Hannibal lost a significant amount of his initiative in the field, being forced to march to and fro protecting his allies from Roman vengeance.