Servius Tulius

Servius Tullius initiated a census during which the population was counted, citizens were identified and the Roman classes categorized both socially and militarily. He did it based on wealth. In all, 80,000 citizens were capable of bearing arms.

Organization of Roman Citizens into Social Classes

| Size of Estate | Social Designation | Size | Arms Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leading men of the state–allocated 10,000 asses from public funds for purchase of a horse; widows responsible for providing 2,000 asses for annual upkeep | Knights |

|

|

| 100,000 asses | First Class |

|

|

| 75,000 to 100,000 asses | Second Class |

|

|

| 50,000 asses | Third Class |

|

|

| 25,000 asses | Fourth Class |

|

|

| 11,000 asses | Fifth Class |

|

|

| Property < 11,000 asses | Rest of society |

|

|

As was often the case, the egalitarian tendencies prevalent under Romulus were replaced by a hierarchical system in which the wealthy were asked to defend the state because they had the most to lose in case of defeat. They were also taxed the most heavily. In return, they were given political and social privileges; the right to vote first in the Assembly, preferred seating and recognition at public events. The leading men of the state were given horses for training as cavalry at public expense. And select widows were responsible for their upkeep.

However, Tullius was not only interested in expanding the state by military means. He also resorted to diplomacy. The king used the construction of a temple to Diana, as representing the entire Latin nation, in Rome to assert primacy of the city over others. The Latins agreed to this symbolic construction.

Nevertheless, Tullius was still challenged regarding his right to kingship. He therefore submitted to a plebiscite which he overwhelmingly won. But the story as written by Livy contains within it hints of deeper social conflict between the classes, the ambition of Tullia, one of Tullius’ daughters, as well as perhaps the anachronism of resentment against the institution of monarchy.

Livy. The History of Rome in Three Volumes by Livy (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) (Kindle Locations 1008-1031). Halcyon Press Ltd.. Kindle Edition.

The Story of Tullia, the Ambitious Daughter of Servius Tullius and the Awakened Ambition of Tarquinius Superbus

Then indeed the old age of Servius began to be every day more disquieted, his reign to be more unhappy. For now the woman looked from one crime to another, and suffered not her husband to rest by night or by day, lest their past murders might go for nothing. “That what she had wanted was not a person whose wife she might be called, or one with whom she might in silence live a slave; what she had wanted was one who would consider himself worthy of the throne; who would remember that he was the son of Tarquinius Priscus; who would rather possess a kingdom than hope for it. If you, to whom I consider myself married, are such a one, I address you both as husband and king; but if not, our condition has been changed so far for the worse, as in that person crime is associated with meanness. Why not prepare yourself? It is not necessary for you, as for your father, (coming here) from Corinth or Tarquinii, to strive for foreign thrones. Your household and country’s gods, the image of your father, and the royal palace, and the royal throne in that palace, constitute and call you king. Or if you have too little spirit for this, why do you disappoint the nation? Why do you suffer yourself to be looked up to as a prince? Get hence to Tarquinii or Corinth. Sink back again to your (original) race, more like your brother than your father.” By chiding him in these and other terms, she spurs on the young man; nor can she herself rest; (indignant) that when Tanaquil, a foreign woman, could achieve so great a project, as to bestow two successive thrones on her husband, and then on her son-in-law, she, sprung from royal blood, should have no weight in bestowing and taking away a kingdom. Tarquinius, driven on by these frenzied instigations of the woman, began to go round and solicit the patricians, especially those of the younger families;[59] reminded them of his father’s kindness, and claimed a return for it; enticed the young men by presents; increased his interest, as well by making magnificent promises on his own part, as by inveighing against the king at every opportunity.

Servius Tullius is overthrown and murdered

At length, as soon as the time seemed convenient for accomplishing his object, he rushed into the forum, accompanied by a party of armed men; then, whilst all were struck with dismay, seating himself on the throne before the senate-house, he ordered the fathers to be summoned to the senate-house by the crier to attend king Tarquinius. They assembled immediately, some being already prepared for the occasion, some through fear, lest their not having come might prove detrimental to them, astounded at the novelty and strangeness of the matter, and considering that it was now all over with Servius. Then Tarquinius, commencing his invectives against his immediate ancestors: “that a slave, and born of a slave, after the untimely death of his parent, without an interregnum being adopted, as on former occasions, without any comitia (being held), without the suffrages of the people, or the sanction of the fathers, he had taken possession of the kingdom as the gift of a woman. That so born, so created king, ever a favorer of the most degraded class, to which he himself belongs, through a hatred of the high station of others, he had taken their land from the leading men of the state and divided it among the very meanest; that he had laid all the burdens, which were formerly common, on the chief members of the community; that he had instituted the census, in order that the fortune of the wealthier citizens might be conspicuous to (excite) public envy, and that all was prepared whence he might bestow largess on the most needy, whenever he might please.” When Servius, aroused by the alarming announcement, came in during this harangue, immediately from the porch of the senate-house, he says with a loud voice, “What means this, Tarquin? By what audacity hast thou dared to summon the fathers or to sit on my throne while I am still alive?” To this, when he fiercely replied “that he, the son of a king, occupied the throne of his father, a much fitter successor to the throne than a slave; that he (Servius) had insulted his masters full long enough by his arbitrary shuffling,” a shout arises from the partisans of both, and a rush of the people into the senate-house took place, and it became evident that whoever came off victor would have the throne. Then Tarquin, necessity itself now obliging him to have recourse to the last extremity, having much the advantage both in years and strength, seizes Servius by the middle, and having taken him out of the senate-house, throws him down the steps to the bottom. He then returns to the senate-house to assemble the senate. The king’s officers and attendants fly. He himself, almost lifeless, when he was returning home with his royal retinue frightened to death, and had arrived at the top of the Cyprian street, is slain by those who had been sent by Tarquin, and had overtaken him in his flight. As the act is not inconsistent with her other marked conduct, it is believed to have been done by Tullia’s advice. Certain it is, (for it is readily admitted,) that driving into the forum in her chariot, and not abashed by the crowd of persons there, she called her husband out of the senate-house, and was the first to style him king; and when, on being commanded by him to withdraw from such a tumult, she was returning home, and had arrived at the top of the Cyprian street, where Diana’s temple lately was, as she was turning to the right to the Orbian hill, in order to arrive at the Esquiline, the person who was driving, being terrified, stopped and drew in the reins, and pointed out to his mistress the murdered Servius as he lay.

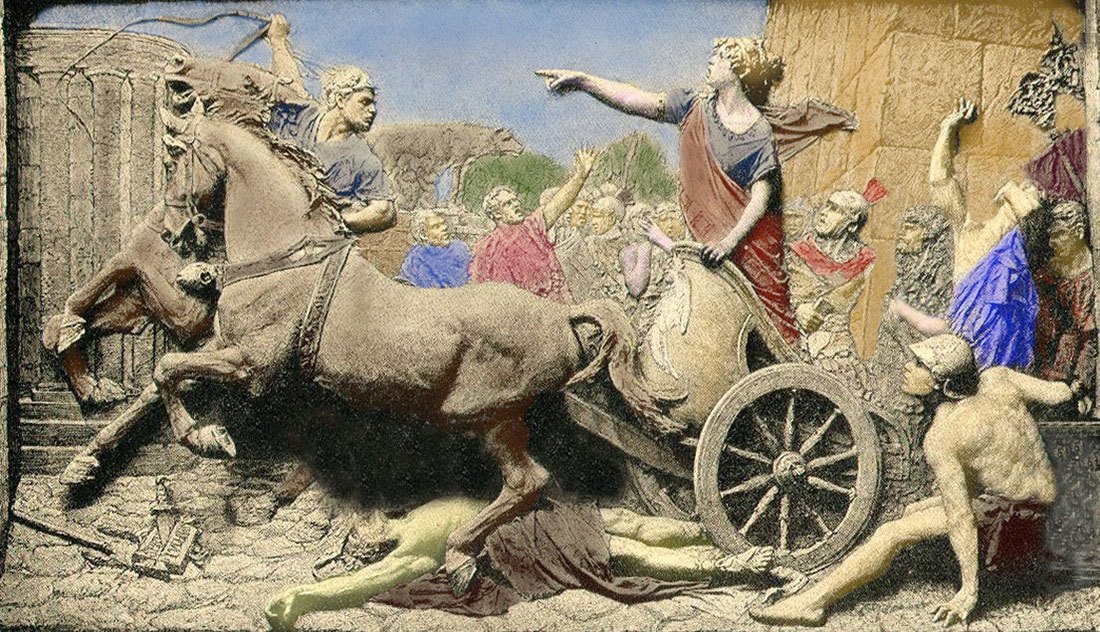

Tullia’s Sacrilege

On this occasion a revolting and inhuman crime is stated to have been committed, and the place is a monument of it. They call it the Wicked Street, where Tullia, frantic and urged on by the furies of her sister and husband, is reported to have driven her chariot over her father’s body, and to have carried a portion of her father’s body and blood to her own and her husband’s household gods, herself also being stained and sprinkled with it; through whose vengeance results corresponding to the wicked commencement of the reign were soon to follow.

Tullia commits sacrilege.

Tullia having helped engineer the overthrow and murder of Servius Tullius, has her driver run over the corpse of her father.

Livy’s Critique of Monarchy

Tullius reigned forty-four years in such a manner that a competition with him would prove difficult even for a good and moderate successor. But this also has been an accession to his glory; that with him perished all just and legitimate reigns. This authority, so mild and so moderate, yet, because it was vested in one, some say that he had it in contemplation to resign, had not the wickedness of his family interfered with him whilst meditating the liberation of his country. After this period Tarquin began his reign, whose actions procured him the surname of the Proud, for he refused his father-in-law burial, alleging that even Romulus died without sepulture. He put to death the principal senators, whom he suspected of having been in the interest of Servius. Then, conscious that the precedent of obtaining the crown by evil means might be adopted from him against himself, he surrounded his person with armed men, for he had no claim to the kingdom except by force inasmuch as he reigned without either the order of the people or the sanction of the senate. To this was added (the fact) that, as he reposed no hope in the affection of his subjects, he found it necessary to secure his kingdom by terror; and in order to strike this into the greater number, he took cognizance of capital cases solely by himself without assessors; and under that pretext he had it in his power to put to death, banish, or fine, not only those who were suspected or hated, but those also from whom he could obtain nothing else but plunder. The number of the fathers more especially being thus diminished, he determined to elect none into the senate, in order that the order might become contemptible by their very paucity, and that they might feel the less resentment at no business being transacted by them. For he was the first king who violated the custom derived from his predecessors of consulting the senate on all subjects; he administered the public business by domestic counsels. War, peace, treaties, alliances, he contracted and dissolved with whomsoever he pleased, without the sanction of the people and senate. The nation of the Latins in particular he wished to attach to him, so that by foreign influence also he might be more secure among his own subjects…

Livy. The History of Rome in Three Volumes by Livy (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) (Kindle Locations 1031-1090). Halcyon Press Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Servius Tullius–Summary

Click edit button to change this text.Tullius reigned forty-four years, according to Livy. He was by any measure a good king. He introduced the census and reorganized Roman society by class and by property requirement. Much like other ancient city states, those with the most property bore the heaviest burden of war. But they also derived political benefits that were formally recognized; such as voting first in the Assembly.

It should be noted that scholars differ on the size and sophistication of the archaic Roman state. Mary Beard in her book SPQR argues that the 80,000 citizen figure that Livy cites is unrealistic, that the number is closer to 20,000. She also raises the question of what “Rex” means in the Roman context of this time. Her contention is that “kings” may have been chieftains and legions may actually have been private militia or gangs and that battles were actually cattle raids.

On the other hand, in reading the articles in Ancient Rome: The Archeology of the Eternal City (edited by Jon Coulston and Hazel Dodge), one gets the sense that the monumental constructions of 6th century archaic Rome (e.g., Cloaca Maxima, Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus) suggest a much larger demographic, political and economic entity.

Ancient Rome: The Archeology of the Eternal City Coulston, Jon and Dodge, Hazel (editors), Oxford University School of Archeology, Oxford, 2000.

Mary Beard SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome Liverlight Publishing Company, NY, NY, WW Norton & Company Ltd. Castle House, London. 2015.