281-272 BC

Pyrrhic War

280 BC – 272 BC

Prologue

The major players in the Pyrrhic war were Epirus, the Roman Republic, and Tarentum, all of Magna Graecia (except Rhegium), Carthage, the Etruscans, the Samnites, the Messapians, the Brutii and the Lucani.

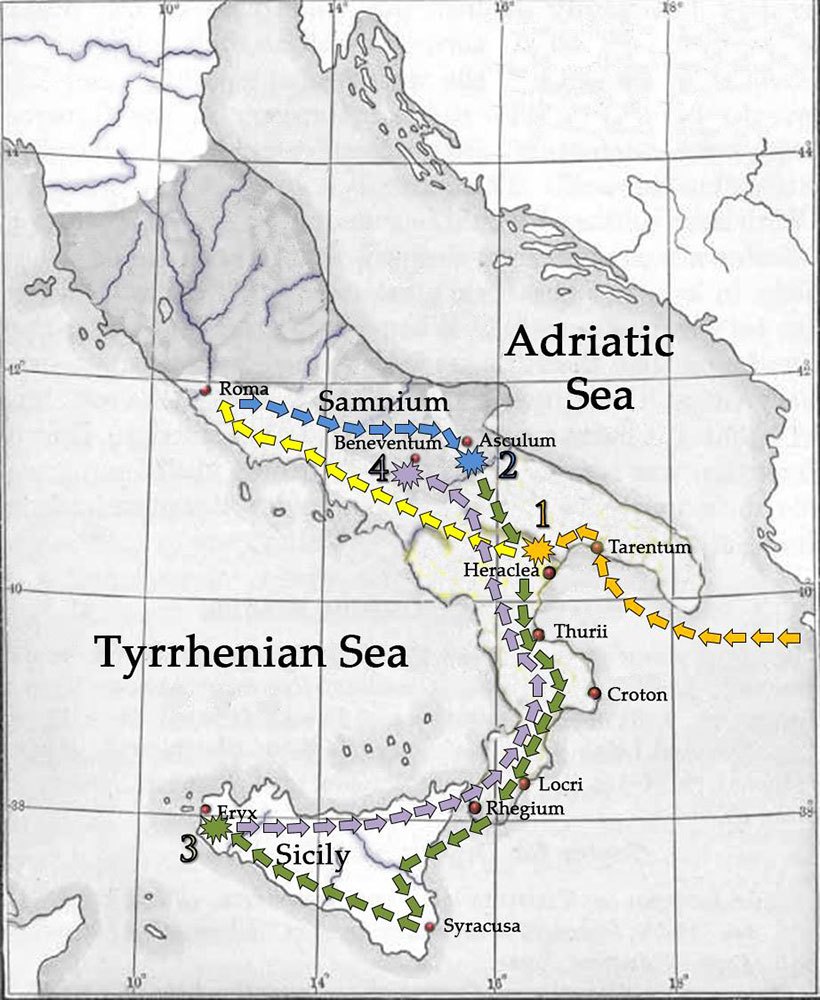

The war can be divided into 4 phases; 1) mobilization and the battle of Heraclea; 2) Offer of peace, the feint toward Rome and the battle of Asculum; 3) the struggle for Sicily, and 4) the return to Italy and the battle of Maleventum (Beneventum).

Pyrrhic War–Key Battles

Map shows the Pyrrhic campaign which begins in southern Italy and the defeat of the Roman Legions at Heraclea (1), then a feint toward Rome and another victory at Asculum (2). Next Pyrrhus swings south into Sicily and forces the Carthaginians into a redoubt on the western end of the island with a victory at Eryx (3) and a failed seige at Lilybaeum. He then returns to Italy to face the Romans again but either loses or achieves a draw at the battle of Maleventum (4), (later renamed Beneventum by the Romans in honor of their success). In 272 BC, Pyrrhus quits Italy, essentially leaving his campaign objectives unrealized.

Pyrrhus Prepares for War: Phase 1

After landing with his army at Tarentum, Pyrrhus began recruiting and organizing his army. The Tarentines had promised 350,000 men at arms.

…the people sent ambassadors to Pyrrhus, not only from their own number, but also from the Italian Greeks. These brought gifts to Pyrrhus, and told him they wanted a leader of reputation and prudence, and that he would find there large forces gathered from Lucania, Messapia, Samnium, and Tarentum, amounting to twenty thousand horse and three hundred and fifty thousand foot all told. This not only exalted Pyrrhus himself, but also inspired the Epeirots with eagerness to undertake the expedition.

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 11924-11928). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition.

However, there was no army in the field at the time of Pyrrhus’ landing. There were garrisons in several Greek towns as well as a weak mobile Roman army in the region. This Roman force threatened Tarentum but the Romans retreated when, expecting a battle with the Tarentines, an advance guard of 3000 Epirotes took the field. This hasty Roman retreat gave Pyrrhus some time to prepare. He would need it. The Tarentines did not want to fight; rather they wished to purchase troops to do their fighting for them. Pyrrhus, comprehending the situation, treated Tarentum as a conquered city.

Pyrrhus, prepared for such opposition, immediately treated Tarentum as a conquered city; soldiers were quartered in the houses, the assemblies of the people and the numerous clubs (—sussitia—) were suspended, the theatre was shut, the promenades were closed, and the gates were occupied with Epirot guards. A number of the leading men were sent over the sea as hostages; others escaped the like fate by flight to Rome. These strict measures were necessary, for it was absolutely impossible in any sense to rely upon the Tarentines. It was only now that the king, in possession of that important city as a base, could begin operations in the field.

Mommsen, Theodor. The History of Rome (Annotated) (Kindle Locations 8314-8319). Kindle Edition.

Pyrrhus forced the Tarentines to join the military levy under penalty of death. The Tarentines ultimately contributed 6,000 hoplites and 1,000 cavalry to Pyrrhus’ army.

Roman Preparations for War: Phase I

The Romans were aware of the threat from Pyrrhus and they took steps to prepare. They secured their allies. The city states that were considered undependable received garrisons. Leaders of opposition parties were either arrested or executed. A war contribution was levied; a full contingent was raised even proletarians who usually did not serve in the army. One Roman army was held in reserve to defend Rome. Another marched up into Etruria and dispersed the armies of the Volsci and Volsinii. The main army, approximately 50,000 strong under the command of Publius Laevinus, headed south toward Magna Graecia. In the meantime a weak Roman force prevented the Samnites and Lucanians from joining up with the Pyrrhic army.

Mommsen, Theodor. The History of Rome (Annotated) (Kindle Locations 8314-8339). Kindle Edition.

Battle of Heraclea–Phase 1

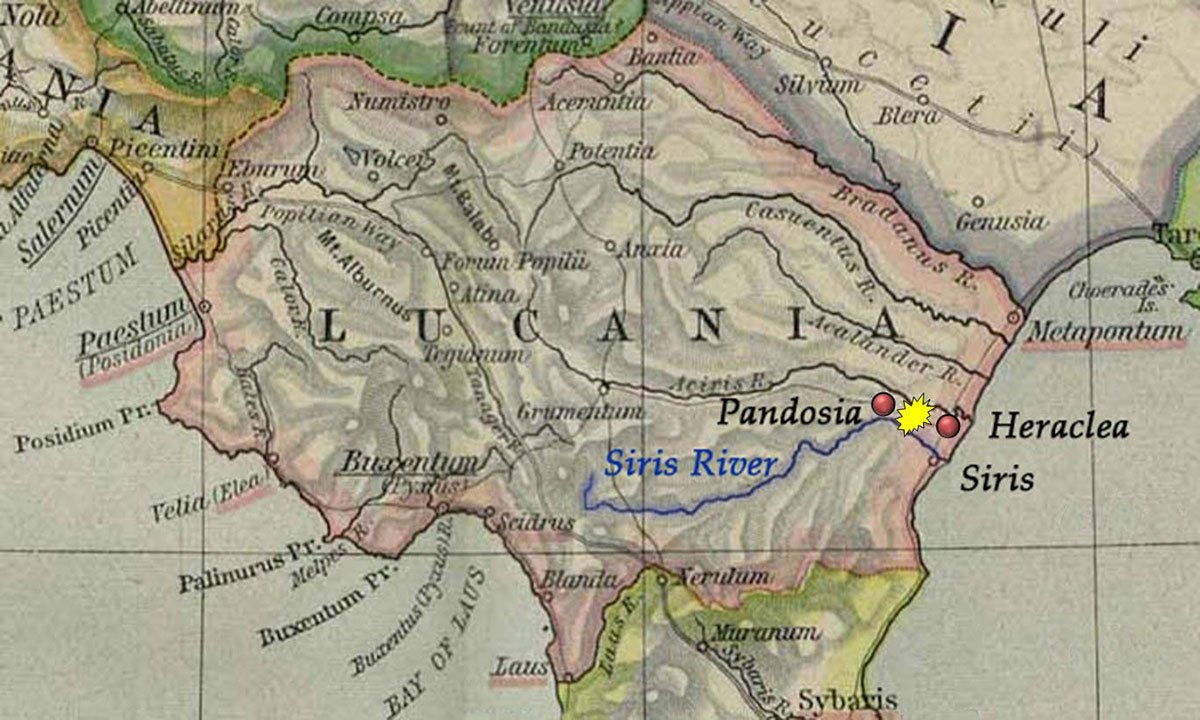

After a rough crossing of the Adriatic Sea, Pyrrhus concentrated his army at Tarentum. He then put Tarentum on a wartime footing and recruited local forces. Those, however, were slow in coming, so Pyrrhus marched south toward the Siris River and positioned his army between the towns of Pandosia and Heraclea. The Romans approached Pyrrhus’ position from the south.

Battle of Heraclea

Pyrrhus positioned his army between Pandosia and Heraclea on the north side of the river Siris. The Romans were encamped on the south side of the river.

Pyrrhus’ army was constituted of the following:

| Number of Troops | Pyrrhus’ Army, 280 BC* |

|---|---|

| 3,000 | Hypaspists |

| 20,000 | Foot-phalangites (includes 5,000 Macedonians) |

| 6,000 | Tarentine levy hoplites |

| 2,000 | Archers |

| 500 | Rhodian slingers |

| 4,000 | Horsemen (includes Thessalians, 1,000 Tarentines) |

| 20 | War elephants |

*Plutarch’s Lives Volume 1. The Dryden Translation. Ed. Arthur Hugh Clough. The Modern Library, Random House, Inc. New York. 1992. Page 530.

Excerpt from Plutarch’s Lives on the battle of Heraclea

And now word was brought to Pyrrhus that Laevinus the Roman consul was coming against him with a large army and plundering Lucania as he came. Pyrrhus had not yet been joined by his allies, but thinking it an intolerable thing to hold back and suffer his enemies to advance any nearer, he took the field with his forces, having first sent a herald to the Romans with the enquiry whether it was their pleasure, before waging war, to receive satisfaction from the Italian Greeks, employing him as arbiter and mediator. But Laevinus made answer that the Romans neither chose Pyrrhus as a mediator nor feared him as a foe. Pyrrhus therefore went forward and pitched his camp in the plain between the cities of Pandosia and Heraclea. When he learned that the Romans were near and lay encamped on the further side of the river Siris, he rode up to the river to get a view of them; and when he had observed their discipline, the appointment of their watches, their order, and the general arrangement of their camp, he was amazed, and said to the friend that was nearest him: “The discipline of these Barbarians is not barbarous; but the result will show us what it amounts to.” He was now less confident of the issue, and determined to wait for his allies; but he stationed a guard on the bank of the river to check the Romans if, in the meantime, they should attempt to cross it. The Romans, however, anxious to anticipate the coming of the forces which Pyrrhus had decided to await, attempted the passage, their infantry crossing the river by a ford, and their cavalry dashing through the water at many points, so that the Greeks on guard, fearing that they would be surrounded, withdrew. When Pyrrhus saw this, he was greatly disturbed, and charging his infantry officers to form in line of battle at once and stand under arms, he himself rode out with his three thousand horsemen, hoping to come upon the Romans while they were still crossing, and to find them scattered and in disorder. But when he saw a multitude of shields gleaming on the bank of the river and the cavalry advancing upon him in good order, he formed his men in close array and led them to the attack. He was conspicuous at once for the beauty and splendor of his richly ornamented armor, and showed by his deeds that his valor did not belie his fame; and this most of all because, while actively participating in the fight and vigorously repelling his assailants, he did not become confused in his calculations nor lose his presence of mind, but directed the battle as if he were surveying it from a distance, darting hither and thither himself and bringing aid to those whom he thought to be overwhelmed. Here Leonnatus the Macedonian, observing that an Italian was intent upon Pyrrhus, and was riding out against him and following him in every movement from place to place, said: “Seest thou, O King, that Barbarian yonder, riding the black horse with white feet? He looks like a man who has some great and terrible design in mind. 9 For he keeps his eyes fixed upon thee and is intent to reach thee with all his might and main, and pays no heed to anybody else. So be on thy guard against the man.” To him Pyrrhus made reply: “What is fated, O Leonnatus, it is impossible to escape; but with impunity neither he nor any other Italian shall come to close quarters with me.” While they were still conversing thus, the Italian levelled his spear, wheeled his horse, and charged upon Pyrrhus. Then at the same instant the Barbarian’s spear smote the king’s horse, and his own horse was smitten by the spear of Leonnatus. Both horses fell, but while Pyrrhus was seized and rescued by his friends, the Italian, fighting to the last, was killed. He was a Frentanian, by race, captain of a troop of horse, Oplax by name. This taught Pyrrhus to be more on his guard; and seeing that his cavalry were giving way, he called up his phalanx and put it in array, while he himself, after giving his cloak and armor to one of his companions, Megacles, and hiding himself after a fashion behind his men, charged with them upon the Romans. But they received and engaged him, and for a long time the issue of the battle remained undecided; it is said that there were seven turns of fortune, as each side either fled back or pursued. And indeed the exchange of armor which the king had made, although it was opportune for the safety of his person, came near overthrowing his cause and losing him the victory. For many of the enemy assailed Megacles and the foremost of them, Dexoüs by name, smote him and laid him low, and then, snatching away his helmet and cloak, rode up to Laevinus, displaying them, and shouting as he did so that he had killed Pyrrhus. Accordingly, as the spoils were carried along the ranks and displayed, there was joy and shouting among the Romans, and among the Greeks consternation and dejection, until Pyrrhus, learning what was the matter, rode along his line with his face bare, stretching out his hand to the combatants and giving them to know him by his voice. At last, when the Romans were more than ever crowded back by the elephants, and their horses, before they got near the animals, were terrified and ran away with their riders, Pyrrhus brought his Thessalian cavalry upon them while they were in confusion and routed them with great slaughter. Dionysius states that nearly fifteen thousand of the Romans fell, but Hieronymus says only seven thousand; on the side of Pyrrhus, thirteen thousand fell, according to Dionysius, but according to Hieronymus less than four thousand. These, however, were his best troops; and besides, Pyrrhus lost the friends and generals whom he always used and trusted most. However, he took the camp of the Romans after they had abandoned it, and won over to his side some of their allied cities; he also wasted much territory, and advanced until he was within three hundred furlongs’ distance from Rome.

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 11779-12021). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition. 2013.

After the Victory of Pyrrhus at Heraclea

Excerpt from Plutarch’s Lives

…Pyrrhus lost the friends and generals whom he always used and trusted most. However, he took the camp of the Romans after they had abandoned it, and won over to his side some of their allied cities; he also wasted much territory, and advanced until he was within three hundred furlongs’ distance from Rome. And now, after the battle, there came to him many of the Lucanians and Samnites. These he censured for being late, but it was clear that he was pleased and proud because with his own troops and the Tarentines alone he had conquered the great force of the Romans.

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 12021-12025). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition. 2013.

Pyrrhus offers the Romans Peace

After Heraclea, the Romans wasted no time in replenishing their depleted legions. Pyrrhus, understanding that taking Rome and subduing the Romans would be no easy task, chose to offer peace in exchange for immunity for the Tarentines. The Senate was inclined to agree when Appius Claudius Caecus (the builder of the Appian Way), now old and blind, had himself carried into the Senate house where he spoke against peace with Pyrrhus.

Appius Claudius Caecus speaks against peace with Pyrrhus

Excerpt from Plutarch’s Lives

“Up to this time, O Romans, I have regarded the misfortune to my eyes as an affliction, but it now distresses me that I am not deaf as well as blind, that I might not hear the shameful resolutions and decrees of years which bring low the glory of Rome. For what becomes of the words that ye are ever reiterating to all the world, namely, that if the great Alexander of renown had come to Italy and had come into conflict with us, when we were young men, and with our fathers, when they were in their prime, he would not now be celebrated as invincible, but would either have fled, or, perhaps, have fallen there, and so have left Rome more glorious still? 2 Surely ye are proving that this was boasting and empty bluster, since ye are afraid of Chaonians and Molossians, who were ever the prey of the Macedonians, and ye tremble before Pyrrhus, who has ever been a minister and servitor to one at least of Alexander’s bodyguards, and now comes wandering over Italy, not so much to help the Greeks who dwell here, as to escape his enemies at home, promising to win for us the supremacy here with that army which could not avail to preserve for him a small portion of Macedonia. 3 Do not suppose that ye will rid yourself of this fellow by making him your friend; nay, ye will bring against you others, and they will despise you as men whom anybody can easily subdue, if Pyrrhus goes away without having been punished for his insults, but actually rewarded for them in having enabled Tarentines and Samnites to mock at Romans.

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 12043-12054). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition. 2013.

The Roman Senate, upon hearing Appius’ speech, refused peace so long as Pyrrhus remained with an army on Italian soil.

Pyrrhus Wins Major Victory at Asculum–Phase 2

Excerpt from Plutarch’s Lives

Pyrrhus…after recuperating his army… marched to the city of Asculum, where he engaged the Romans. Here, however, he was forced into regions where his cavalry could not operate, and upon a river with swift current and wooded banks, so that his elephants could not charge and engage the enemy’s phalanx. Therefore, after many had been wounded and slain, for the time being the struggle was ended by the coming of night. But on the next day, designing to fight the battle on level ground, and to bring his elephants to bear upon the ranks of the enemy, Pyrrhus occupied betimes the unfavourable parts of the field with a detachment of his troops; then he put great numbers of slingers and led his forces to the attack in dense array and with a mighty impetus. So the Romans, having no opportunity for sidelong shifts and counter-movements, as on the previous day, were obliged to engage on level ground and front to front; and being anxious to repulse the enemy’s men-at arms before their elephants came up, they fought fiercely with their swords against the Macedonian spears, reckless of their lives and thinking only of wounding and slaying, while caring naught for what they suffered. After a long time, however, as we are told, they began to be driven back at the point where Pyrrhus himself was pressing hard upon his opponents; but the greatest havoc was wrought by the furious strength of the elephants, since the valor of the Romans was of no avail in fighting them, but they felt that they must yield before them as before an onrushing billow or a crashing earthquake, and not stand their ground only to die in vain, or suffer all that is most grievous without doing any good at all. After a short flight the Romans reached their camp, with a loss of six thousand men, according to Hieronymus, who also says that on the side of Pyrrhus, according to the king’s own commentaries, thirty-five hundred and five were killed. Dionysius, however, makes no mention of two battles at Asculum, nor of an admitted defeat of the Romans, but says that the two armies fought once for all until sunset and then at last separated; Pyrrhus, he says, was wounded in the arm by a javelin, and also had his baggage plundered by the Daunians; and there fell, on the side of Pyrrhus and on that of the Romans, over fifteen thousand men. The two armies separated; and we are told that Pyrrhus said to one who was congratulating him on his victory, “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined.” For he had lost a great part of the forces with which he came, and all his friends and generals except a few; moreover, he had no others whom he could summon from home, and he saw that his allies in Italy were becoming indifferent, while the army of the Romans, as if from a fountain gushing forth indoors, was easily and speedily filled up again, and they did not lose courage in defeat, nay, their wrath gave them all the more vigor and determination

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 12098-12120). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition. 2013.

Pyrrhus Invades Sicily–Phase 3

As Pyrrhus was besting the Romans in the field, the Greek cities of Sicily were begging his help in driving out the Carthaginians. Because Sicily was a strategic objective after the defeat of the Romans and because possession of Macedonia was his ultimate goal, Pyrrhus thought that the time to make a decision concerning either was at hand. Ultimately, he calculated that his chances of success were better in Sicily because that is where he decided to go.

Excerpt from Plutarch’s Lives

…there came to him [Pyrrhus] from Sicily men who offered to put into his hands the cities of Agrigentum, Syracuse, and Leontini, and begged him to help them to drive out the Carthaginians and rid the island of its tyrants; and from Greece, men with tidings that Ptolemy Ceraunus with his army had perished at the hands of the Gauls, and that now was the time of all times for him to be in Macedonia, where they wanted a king. Pyrrhus rated Fortune soundly because occasions for two great undertakings had come to him at one time, and thinking that the presence of both meant the loss of one, he wavered in his calculations for a long time. Then Sicily appeared to offer opportunities for greater achievements, since Libya was felt to be near, and he turned in this direction, and forthwith sent out Cineas to hold preliminary conferences with the cities, as was his wont, while he himself threw a garrison into Tarentum. The Tarentines were much displeased at this, and demanded that he either apply himself to the task for which he had come, namely to help them in their war with Rome, or else abandon their territory and leave them their city as he had found it. To this demand he made no very gracious reply, but ordering them to keep quiet and await his convenience, he sailed off. On reaching Sicily, his hopes were at once realized securely; the cities readily gave themselves up to him, and wherever force and conflict were necessary nothing held out against him at first, but advancing with thirty thousand foot, twenty-five hundred horse, and two hundred ships, he put the Phoenicians to rout and subdued the territory under their control. Then he determined to storm the walls of Eryx, which was the strongest of their fortresses and had numerous defenders. So when his army was ready, he put on his armor, went out to battle, and made a vow to Heracles that he would institute games and a sacrifice in his honor, if the god would render him in the sight of the Sicilian Greeks an antagonist worthy of his lineage and resources; then he ordered the trumpets to sound, scattered the Barbarians with his missiles, brought up his scaling-ladders, and was the first to mount the wall. Many were the foes against whom he strove; some of them he pushed from the wall on either side and hurled them to the ground, but most he lay dead in heaps about him with the strokes of his sword. He himself suffered no harm, but was a terrible sight for his enemies to look upon, and proved that Homer was right and fully justified in saying that valor, alone of the virtues, often displays transports due to divine possession and frenzy. After the capture of the city, he sacrificed to the god in magnificent fashion and furnished spectacles of all sorts of contests.

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 12121-12140). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition. 2013.

Pyrrhus Deals with the Mamertines

Excerpt from Plutarch’s Lives

The Barbarians about Messana, called Mamertines, were giving much annoyance to the Greeks, and had even laid some of them under contribution. They were numerous and warlike, and therefore had been given a name which, in the Latin tongue, signifies martial. Pyrrhus seized their collectors of tribute and put them to death, then conquered the people themselves in battle and destroyed many of their strongholds.

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 12140-12145). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition. 2013.

Pyrrhus Refuses Carthaginian Peace Offer, Fails to take Lilybaeum, Loses Loyalty of the Sicilians

Excerpt from Plutarch’s Lives

…when the Carthaginians were inclined to come to terms and were willing to pay him money and sent him ships in case friendly relations were established, he replied to them (his heart being set on greater things) that there could be no settlement or friendship between himself and them unless they abandoned all Sicily and made the Libyan Sea a boundary between themselves and the Greeks. But now, lifted up by his good fortune and by the strength of his resources, and pursuing the hopes with which he had sailed from home in the beginning, he set his heart upon Libya first; and since many of the ships that he had were insufficiently manned, he began to collect oarsmen, not dealing with the cities in an acceptable or gentle manner, but in a lordly way, angrily putting compulsion and penalties upon them. He had not behaved in this way at the very beginning, but had even gone beyond others in trying to win men’s hearts by gracious intercourse with them, by trusting everybody, and by doing nobody any harm. But now he ceased to be a popular leader and became a tyrant, and added to his name for severity a name for ingratitude and faithlessness. Nevertheless the Sicilians put up with these things as necessary, although they were exasperated; but then came his dealings with Thoenon and Sosistratus. These were leading men in Syracuse, and had been first to persuade Pyrrhus to come into Sicily. Moreover, after he had come, they immediately put their city into his hands and assisted him in most of what he had accomplished in Sicily. And yet he was willing neither to take them with him nor to leave them behind, and held them in suspicion. Sosistratus took the alarm and withdrew; but Thoenon was accused by Pyrrhus of complicity with Sosistratus and put to death. With this, the situation of Pyrrhus was suddenly and entirely changed. A terrible hatred arose against him in the cities, some of which joined the Carthaginians, while others called in the Mamertines. And now, as he saw everywhere secessions and revolutionary designs and a strong faction opposed to him, he received letters from the Samnites and Tarentines, who had been excluded from all their territories, could with difficulty maintain the war even in their cities, and begged for his assistance. This gave him a fair pretext for his sailing away, without its being called a flight or despair of his cause in the island; but in truth it was because he could not master Sicily, which was like a storm-tossed ship, but desired to get out of her, that he once more threw himself into Italy. And it is said that at the time of his departure looked back at the island and said to those about him: “My friends, what a wrestling ground for Carthaginians and Romans we are leaving behind us!” And this conjecture of his was soon afterwards confirmed. But the Barbarians combined against him as he was setting sail. With the Carthaginians he fought a sea-fight in the strait and lost many of his ships, but escaped with the rest to Italy; and here the Mamertines, more than ten thousand of whom had crossed in advance of him, though they were afraid to match forces with him, yet threw his whole army into confusion by setting upon him and assailing him in difficult regions. Two of his elephants fell, and great numbers of his rearguard were slain. Accordingly, riding up in person from the van, he sought to ward off the enemy, and ran great risks in contending with men who were trained to fight and were inspired with high courage. And when he was wounded on the head with a sword and withdrew a little from the combatants, the enemy was all the more elated. One of them ran forth far in advance of the rest, a man who was huge in body and resplendent in armor, and in a bold voice challenged Pyrrhus to come out, if he were still alive. This angered Pyrrhus, and wheeling round in spite of his guards, he pushed his way through them — full of wrath, smeared with blood, and with a countenance terrible to look upon, and before the Barbarian could strike dealt him such a blow on his head with his sword that, what with the might of his arm and the excellent temper of his steel, it cleaved its way down through, so that at one instant the parts of the sundered body fell to either side. This checked the Barbarians from any further advance, for they were amazed and confounded at Pyrrhus, and thought him some superior being. So he accomplished the rest of his march unmolested and came to Tarentum, bringing twenty thousand foot and three thousand horse. Then, adding to his force the best troops of the Tarentines, he forthwith led them against the Romans, who were encamped in the country of the Samnites.

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 12145-12179). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition.

Pyrrhus Returns to Italy and Fights the romans at Maleventum (Beneventum)–Phase 4

Excerpt from Plutarch’s Lives

…the power of the Samnites had been shattered, and their spirits were broken, in consequence of many defeats at the hands of the Romans. They also cherished considerable resentment against Pyrrhus because of his expedition to Sicily; hence not many of them came to join him. Pyrrhus, however, divided his army into two parts, sent one of them into Lucania to attack the other consul, that he might not come to the help of his colleague, and led the other part himself against Manius Curius, who was safely encamped near the city of Beneventum and was awaiting assistance from Lucania; in part also it was because his soothsayers had dissuaded him with unfavourable omens and sacrifices that he kept quiet. Pyrrhus, accordingly, hastening to attack this consul before the other one came up, took his best men and his most warlike elephants and set out by night against his camp. But since he took a long circuit through a densely wooded country, his lights did not hold out, and his soldiers lost their way and straggled. This caused delay, so that the night passed, and at daybreak he was in full view of the enemy as he advanced upon them from the heights, and caused much tumult and agitation among them. Manius, however, since the sacrifices were propitious and the crisis forced action upon him, led his forces out and attacked the foremost of the enemy, and after routing these, put their whole army to flight, so that many of them fell and some of their elephants were left behind and captured. This victory brought Manius down into the plain to give battle; here, after an engagement in the open, he routed the enemy at some points, but at one was overwhelmed by the elephants and driven back upon his camp, where he was obliged to call upon the guards, who were standing on the parapets in great numbers, all in arms, and full of fresh vigor. Down they came from their strong places, and hurling their javelins at the elephants compelled them to wheel about and run back through the ranks of their own men, thus causing disorder and confusion there. This gave the victory to the Romans and at the same time the advantage also in the struggle for supremacy. For having acquired high courage and power and a reputation for invincibility from their valor in these struggles, they at once got control of Italy, and soon afterwards of Sicily. Thus Pyrrhus was excluded from his hopes of Italy and Sicily, after squandering six years’ time in his wars there, and after being worsted in his undertakings, but he kept his brave spirit unconquered in the midst of his defeats; and men believed that in military experience, personal prowess, and daring, he was by far the first of the kings of his time, but that what he won by his exploits he lost by indulging in vain hopes, since through passionate desire for what he had not he always failed to establish securely what he had. For this reason Antigonus used to liken him to a player with dice who makes many fine throws but does not understand how to use them when they are made.

Plutarch. Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated) (Delphi Ancient Classics Book 13) (Kindle Locations 12179-12202). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition. 2013.